Overview of Mycoplasma Mastitis

Arthritis caused by M. bovis

Photo courtesy of Dr. Robin Nicholas

Many Mycoplasma species have been isolated from cattle with different diseases. Typically, Mycoplasmas play a secondary role in infections, worsening a pre-existing disease. However, it has been shown that Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis) can play a primary role. M. bovis is considered one of the more pathogenic species and is the most common Mycoplasma pathogen of mastitis in cattle.

M. bovis is an unusual organism. Not only does it cause mastitis, but it affects other body sites in the cow. Often when an M. bovis mastitis outbreak occurs, it will be accompanied by cases of pneumonia, lameness, arthritis, metritis or, in some cases, vaginitis.

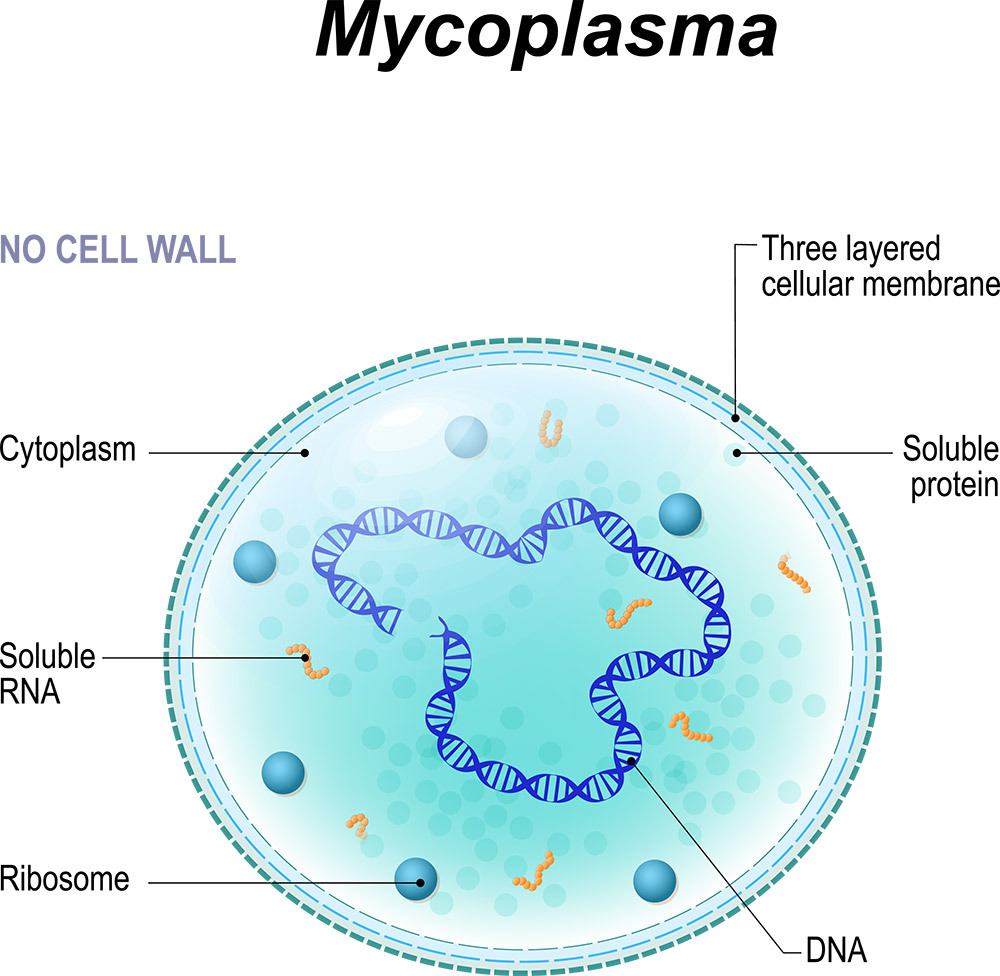

Mycoplasma is very slow growing, which gives it another advantage towards antibiotics apart from the lack of a cell wall because some antibiotics focus on the metabolism and reproduction aspects of the cells. Slow growing bacteria are not reproducing or metabolizing as fast, making them more resistant to antibiotics.

Incidence and Cost

“

20% of 500+ cow herds in the U.S. will have a positive Mycoplasma mastitis bulk tank annually

”

The cause of Mycoplasma mastitis is due to decreased milk production, implementing new control procedures, diagnosis and treatment. M. bovis tends to be chronic, so the cost per case is typically high compared to other pathogens. Animal welfare must also be considered with M. bovis infections, given the chronic nature of the disease and poor to no response to treatment.

The cost of M. bovis in cattle due to mastitis is estimated at US$108 million annually with infection rates of up to 70% of a herd, for pneumonia and related respiratory illnesses at US$32 million annually. Total M. bovis estimated disease cost is at least US$140 million annually in the U.S. Even higher losses – estimated at €144 to €192 million - have been reported in Europe.

The M. bovis outbreak in New Zealand that began in July 2017 has operational costs of the program (through April 2018) at $25.6 million (NZ$35 million) and compensation liabilities at $44 million (NZ$60 million). The New Zealand government has approved $62 million (NZ$85 million) and industry associations have committed $8.2 million (NZ$11.2 million) in response funding to help cover the program costs.

While some countries experience very low rates of infection, M. bovis is in every country in the world. But a lack of M. bovis detection and awareness has been a problem in the past.

Mycoplasma consultant Dr. Robin Nicholas doesn’t believe mycoplasma has been consistently reported in the past partly because they are not an easy pathogen to culture. Unfortunately, in diagnostic labs around the world, there haven’t been many people involved in the diagnosis and search for mycoplasma who have understood how to handle and culture it. Now there are new tools that make it easier to test, and we have increased the awareness of mycoplasma, he said.

Risk Factors

Introduction of new animals - although definitive research studies are not complete, data indicates a strong correlation from newly introduced cattle that are either clinically infected or subclinically infected with the Mycoplasma agent

Stress - corticoids, a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal cortex, become elevated during stressful events like parturition or changes in weather and can cause a cow to erupt with a full-blown clinical infection

Herd size – Improper cleaning, more animal movement, including replacements, equipment shared between more animals and short time for cleaning between animal

Spread and Prevention

Mycoplasma is considered a contagious agent. It isn't only transmitted in the milking parlor, but it's also transmitted from nose to nose contact between cows. The nasal area is the site of Mycoplasma colonization, including the nares, nose and nostril area. It'll pass from cow to cow or calf to calf with the reservoir being the infected cows.

To limit the spread of Mycoplasma mastitis, strict milking time procedures are required including:

- Disinfection of the teats prior to milking

- Use of a single service towel to clean the cow's teats off

- Use of latex gloves that can be easily cleaned between milkings

- Use of a post-milking teat disinfection procedure

- Milking units should be flushed with either a large volume of water or with disinfectant

Treatment

As noted earlier, because of the cell structure of mycoplasmas and their slow growth, most antibiotics do not kill them. Thus, culling is the typical choice, but it is not the only option.

According to a published review article, Mycoplasma mastitis in cattle: To cull or not to cull, authored by Robin Nicholas, Larry Fox and Inna Lysnyansky, if early diagnosis of an outbreak is possible, immediate separation of clinical cases is recommended and cows should be culled if cases don’t improve. However, late diagnosis, often due to the difficulty in detecting mycoplasma, is more problematic.

The authors recommend the following approach to monitor and treat herds:

- Sample bulk tank milk weekly to rapidly identify infected cows and to monitor success of management changes

- Clean and disinfect milking equipment between milking sessions

- Test milk samples from all cows before they enter or re-enter the lactating herd

- If possible, rapidly segregate cows found to be mycoplasma positive or showing mycoplasma mastitis to hospital pens and carefully monitor contacts

- Cull cows where welfare is compromised

- Antibiotic treatment should be discouraged when M. bovis has been confirmed

- Once infected, cows should remain segregated for life unless milk is shown to be M. bovis-free over three successive monthly phases of testing

- Where M. bovis is suspected or confirmed, waste milk should be discarded or pasteurized before feeding to calves