Mastitis

Matters

20% of 500+ cow herds in the U.S. will have a positive Mycoplasma mastitis bulk tank annually*

* U.S. National Animal Health Monitoring Service survey

Where is mastitis found?

Everywhere. Wherever there are dairy cows in the world, there’s mastitis.

A recent USDA survey reported almost all U.S. dairies — 99.7% — reported having at least one case of mastitis during 2013. The report also highlighted that clinical mastitis was detected in about one-fourth of all cows.

According to a 2016 published article , mastitis affects 50% of the dairy herd population in India, 47.5% of the herd population in Pakistan and 51.3% of cows in Bangladesh. Mastitis affects 54.3% of dairy cows in Zhejiang province of China and 52.5% of dairy cows, due to Staphylococcus aureus infection, in Assuite, Egypt.

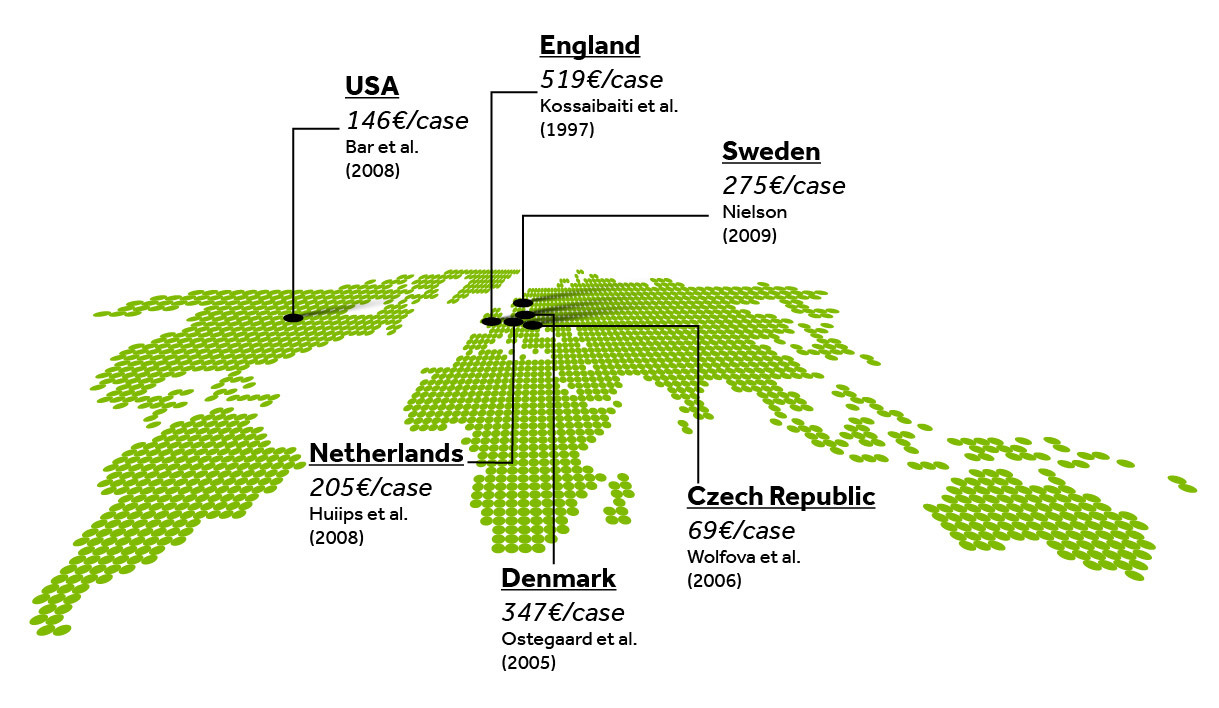

How much does mastitis cost dairy producers annually?

Mastitis is estimated to cost the global dairy industry US$19.7 to US$32 billion annually, according to an article published by the University of Glasgow. The US alone estimates it loses US$2 billion to mastitis in dairy annually. According to a University of Montreal study, mastitis costs the Canadian dairy industry CA$400 million (US$310 million) annually or about CA$500 - $1000 (US$385 - $770) per cow annually.

Cost of mastitis

Diagnosis

When mastitis is identified in a cow’s quarter(s), it is important to identify the pathogen causing the infection because different categories of pathogens require different management strategies. Without a diagnosis, there is no way to know if a given antibiotic will work. However, once you know the infection agent, a dairy farmer can work with his or her veterinarian to target an effective treatment plan. Prudent use of antibiotics reduces the likelihood of resistant pathogens developing and can reduce the duration of treatment a cow may need which decreases operation costs.

Mycoplasma spp.

Overview of Mycoplasma Mastitis

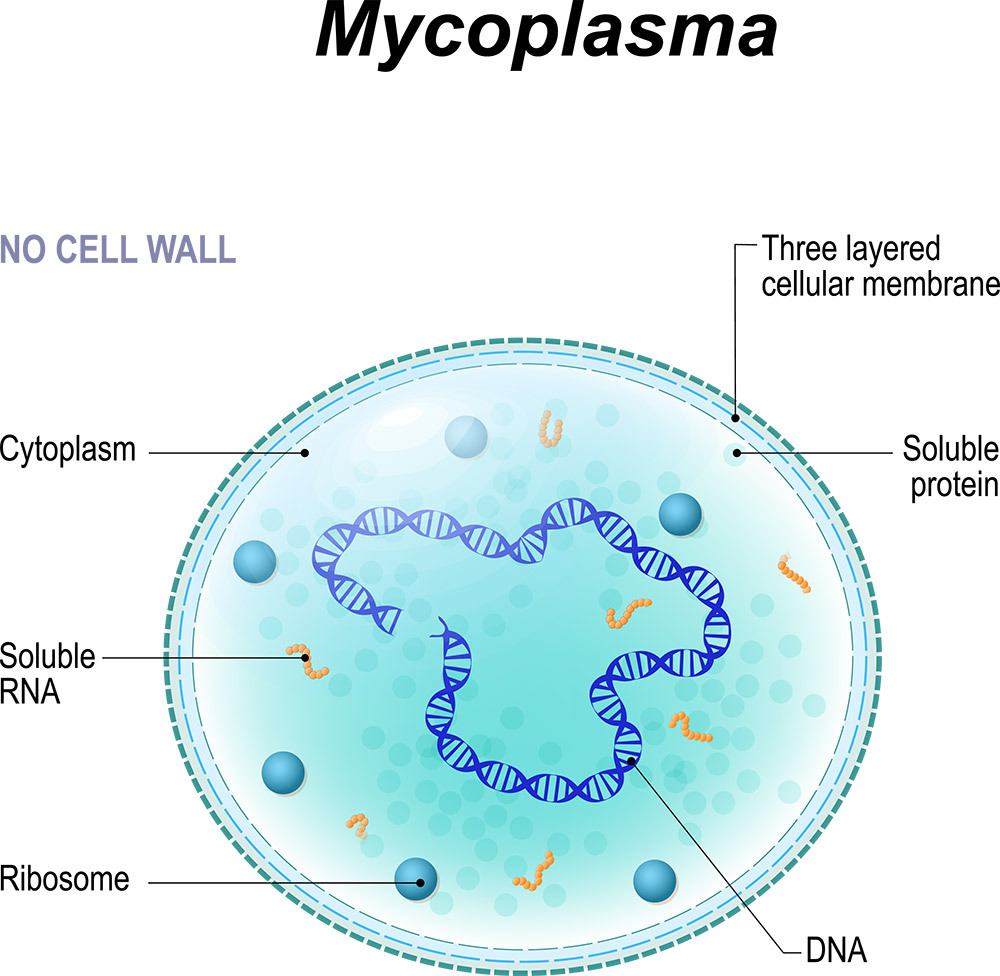

Many Mycoplasma species have been isolated from cattle with different diseases. Typically, Mycoplasmas play a secondary role in infections, worsening a pre-existing disease. However, it has been shown that Mycoplasma bovis ( M. bovis ) can play a primary role. M. bovis is considered one of the more pathogenic species and is the most common Mycoplasma pathogen of mastitis in cattle.

M. bovis is an unusual organism. Not only does it cause mastitis, but it affects other body sites in the cow. Often when an M. bovis mastitis outbreak occurs, it will be accompanied by cases of pneumonia, lameness, arthritis, metritis or, in some cases, vaginitis.

Mycoplasma is very slow growing, which gives it another advantage towards antibiotics apart from the lack of a cell wall because some antibiotics focus on the metabolism and reproduction aspects of the cells. Slow growing bacteria are not reproducing or metabolizing as fast, making them more resistant to antibiotics.

Prototheca spp.

Prototheca zopfii

Credit: Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences –

University of Copenhagen - Denmark

Prototheca Mastitis Incidence Increasing

Prototheca mastitis has recently become an emerging disease. Once thought to be a problem only for dairies in tropical regions, the incidence of this invisible pathogen is now increasing steadily internationally.

For example, a 2019 study published in the Journal of Dairy Science indicated Prototheca zopfii (genotype 2) is the third most common mastitis pathogen in southeast Poland.

A study (P. Moroni, Diseases of the Teats and Udder , Rebhun's Diseases of Dairy Cattle, 2018.) of a large confinement operation in Germany involving 248 Prototheca-infected cows showed:

- 74% of the cows had clinical signs of mastitis

- 80 cows were identified as infected from a whole-herd survey but without a history of clinical mastitis

- 27% of the cows were infected in more than one quarter

Klebsiella spp.

Klebsiella and E. coli – Difficult to Differentiate

Some mastitis pathogens can’t easily be discriminated on culture plates, making a diagnosis difficult. Klebsiella and E. coli are two such Gram-negative pathogens that are known to look very similar, both form large mucoid colonies, and therefore can be easily mistaken for one another when using culture, potentially causing a misdiagnosis if additional tests are not administered. The treatment options for these two pathogens are very different, and a more advanced diagnostic tool, like PCR testing, can offer a clear answer to a farmer’s mastitis problem.

Upclose of

Escherichia coli

colonies.

Credit:

www.vetbact.org

and Lise-Lotte Fernström (BVF, SLU) and Karl-Erik Johansson (BVF, SLU)

Large mucoid colonies of

Klebsiella

oxytoca.

Credit:

www.vetbact.org

and Ingrid Hansson (SVA) and Karl-Erik Johansson (BVF, SLU and SVA)

About 3% to 5% of all mastitis samples contain Klebsiella , but Klebsiella mastitis infections are increasing in several countries around the world. While Klebsiella isn’t as common as E. coli , the economic impact Klebsiella can have on a dairy herd may be more devastating because of the lack of treatment options. Most cows diagnosed with Klebsiella develop chronic mastitis and are culled due to high cell counts or end up dying. Thus, an accurate diagnosis upfront is critical to bring somatic cell counts (SCC) down and remove Klebsiella from the herd.

Impact of Mastitis

Udder Health

Somatic cell count (SCC) is the total number of cells found per milliliter in milk. SCC is mainly composed of white blood cells which are produced by the cow’s immune system to prevent and fight mastitis-causing infection.

According to the UK’s AHDB, generally speaking for every 100,000 cells/ml increase in bulk milk somatic cell count (BMSCC), about 8% to 12% of the dairy herd is likely to be infected - i.e. a dairy herd with a BMSCC of 200,000 cells/ml would be expected to have about 20% of the cows infected at any one time.

Furthermore, a high bulk tank SCC can be used as the first step in diagnostic testing, especially if individual cow data is not available to identify the disease(s).

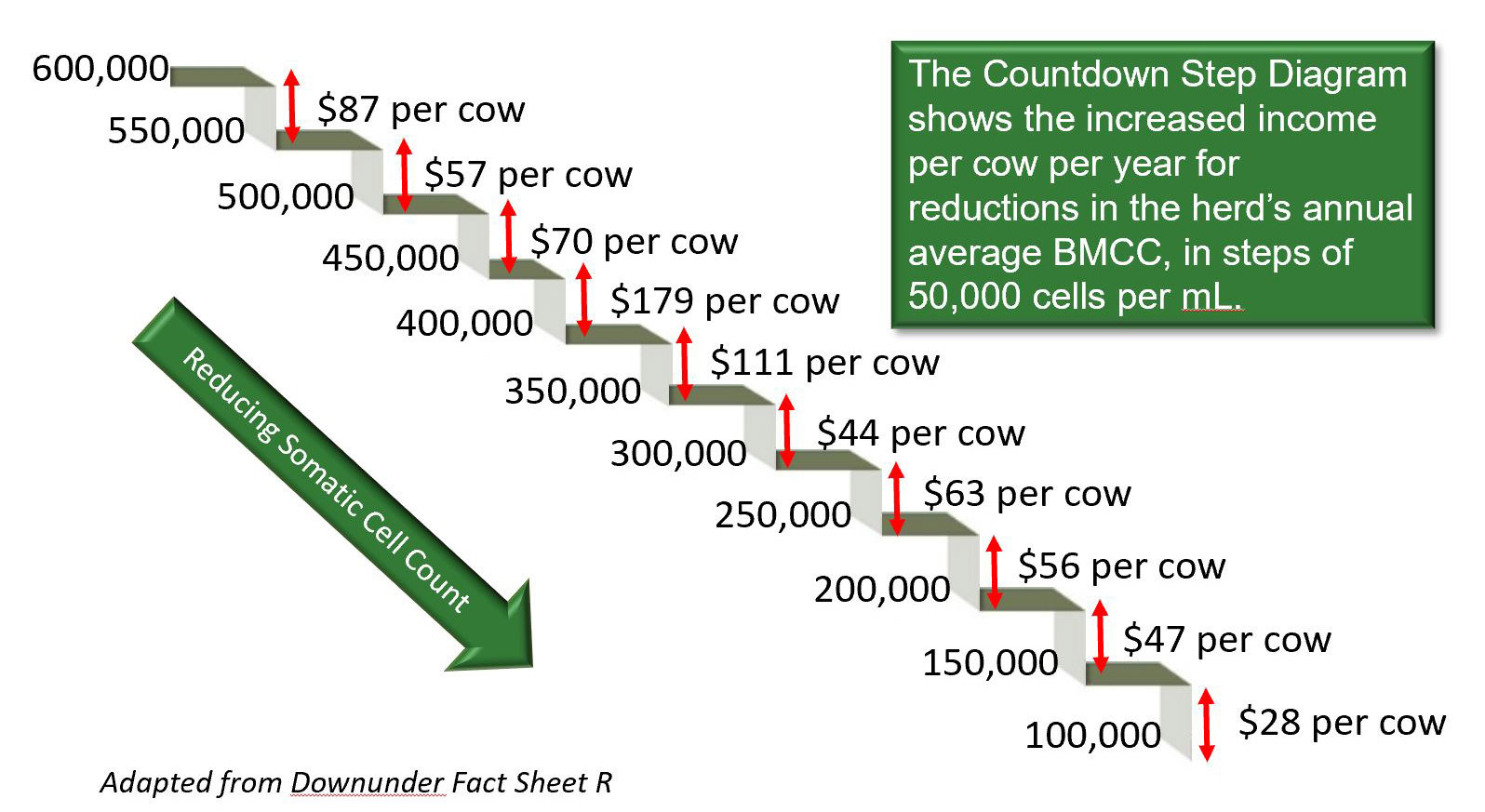

As the economic model developed by the Dairy Australia Countdown Downunder team shows, by reducing the herd SCC the producer’s gain per cow goes up dramatically. This is due to improved milk production, additional milk premiums, reduced costs of clinical treatment and reduced culling. While investing in udder health and mastitis prevention takes considerable effort, the payoff (shown in Australian Dollars) is considerable.

Producers should work with their veterinarian to develop management strategies to improve the udder health in the herd.

Current exchange rate AU$1.00 = US$0.76

Antibiotic Use

Until recently in some parts of the world, common practice was to automatically use a broad-spectrum antibiotic to treat a sick dairy cow or group of cows. However, that practice is changing. Diagnostics are helping to play a vital role in managing antibiotic resistance simply by identifying a specific target.

A diagnostic test identifies the specific bacterial pathogen causing the clinical mastitis signs, and that information allows veterinarians to know the specific antibiotic to prescribe to control or eradicate the pathogen. This enables a more targeted, prudent use of antibiotics, which can help the entire industry manage the issue of antibiotic resistance.

Mastitis is a good example. Due to antibiotics being effective only against specific mastitis pathogens, a diagnosis is necessary (See Mastitis-causing Pathogens and Antimicrobial Use for more details). For example, there is no treatment for M. bovis , so it’s critical to wait for the results of the diagnostic test. Producers wouldn’t want to invest in a treatment for a cow that will most likely be culled immediately. Plus, it would not be considered prudent use of an antibiotic to treat a cow that will ultimately be culled.

As diagnostic tools become faster and more affordable, more and more dairy farmers are choosing to wait and test before they treat.

Resource Materials

- Protect herd health and productivity with PCR

- Emerging Mastitis Threats on Dairy Industry

- Mycoplasma Mastitis and Prevention

- Handling a Herd Mastitis Problem

- Guidelines to Culling Cows with Mastitis

- 15 Ways to Reduce SCC

- Achieving a Health Herd

- The Role of Milking Equipment in Mastitis

- Making Dry Off Count: Combating Mastitis

- Proactive Mastitis Management For Cow Longevity

- Mycoplasma mastitis in cattle: To cull or not to cull

- Mycoplasma mastitis: An emerging disease concern

- Lessons learned from New Zealand’s Mycoplasma bovis outbreak