How to read cattle mineral tags

Learn more how to choose the correct minerals for your cattleMinerals are essential for beef cattle in all stages of production. Understanding how to choose the correct mineral for your cattle can be challenging. This article will provide an overview of how to read mineral tags.

There are six classes of nutrients that all animals require: carbohydrates, fat, protein, vitamins, minerals, and water. While we may not think about it every day, carbohydrates and fats supply the bulk of the energy most animals need and protein is essential for growth, including muscle. Vitamins, minerals, and water often only get attention when the operation does not run smoothly.

Of the six classes of nutrients, minerals are the only inorganic portion of an animal's diet. From an analytical standpoint, such as feedstuffs analysis from DairyOne, Cumberland Valley Analytical Services, or any other lab, the mineral fraction is lumped together in a term called "ash."

This means that the minerals are the noncombustible (that part that cannot be burned) part of the feed. In most feeds, the ash concentration is around 4 to 6% of the total feed. Some hay samples may have as much as 10 to 14% ash, particularly if the hay rake was set close to the ground or the field was dusty. In general, minerals make up a relatively small percentage of beef cattle rations. So why the emphasis on minerals?

Problems can arise when producers do not pay regular attention to their mineral program. Minerals impact a number of functions throughout the body of our cattle. Proper mineral supplementation ensures that cows breed back quickly to produce a calf the following year. Adequate mineral supplementation can also optimize growth in feeder calves. Good mineral balance is critical to developing the structure (or bones) of young stock. As such, minerals must be fed to every class of cattle throughout their lives.

Macro and micro minerals

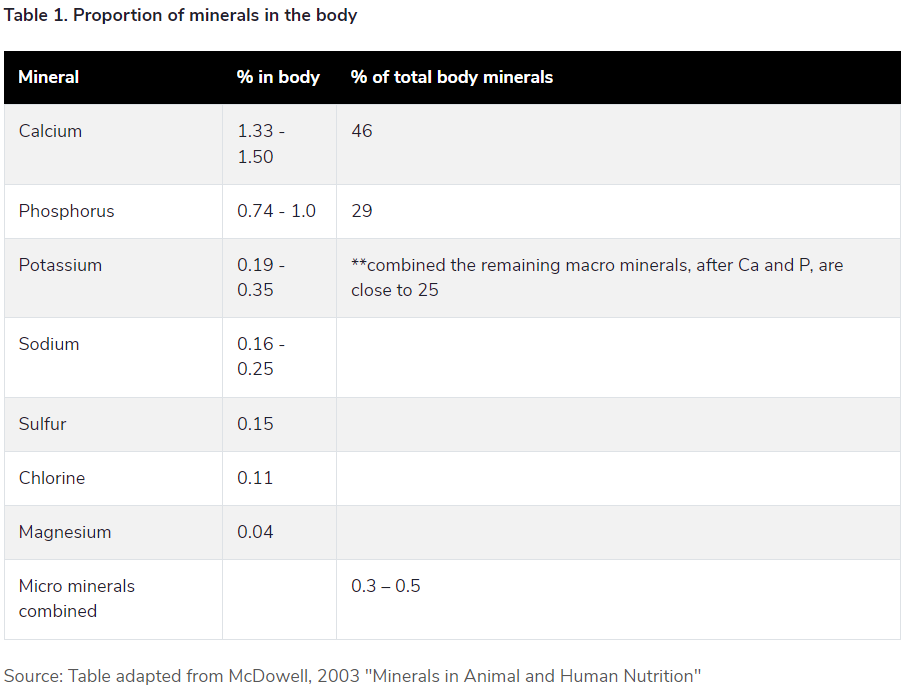

There are two classifications that minerals fall into: macro minerals and micro minerals. The seven macro minerals that function throughout the body are: calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sodium (Na), sulfur (S), chlorine (Cl), and magnesium (Mg). While there are a large number of micro minerals, those most commonly associated with cattle requirements or disorders are: cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), iodine (I), manganese (Mn), molybdenum (Mo), selenium (Se), and zinc (Zn).

These mineral sub-classifications exist based on the proportion of minerals in the body (Table 1). The macro minerals make up over 99% of the body’s total minerals while the micro minerals, sometimes referred to as trace minerals, make up less than 1% of the body’s total minerals.

Mineral functions

The discrepancy between the amount of macro minerals and micro minerals may encourage one to place a greater emphasis on the macro minerals. However, the reality is that a number of critical functions would be impacted if due attention was not given to the micro minerals. That is because each mineral plays a key part in different body system functions. While this list is not meant to be exhaustive, some highlights of those functions are included.

For example, macro minerals, like calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P), are critical for bone growth and muscle contractions. Meanwhile, sodium (Na) and potassium (K) are important for what we call osmotic balance, making sure the body, which is largely water, stays hydrated so that it can function.

Micro minerals, like copper (Cu) and Zinc (Zn) are critical in pathways throughout the body that support energy supply to the animal. Many of the micro minerals, including Cu and Zn but also selenium (Se) and manganese (Mn), support reproductive and immune functions of the body, ensuring that cattle are healthy and cows get bred and stay pregnant!

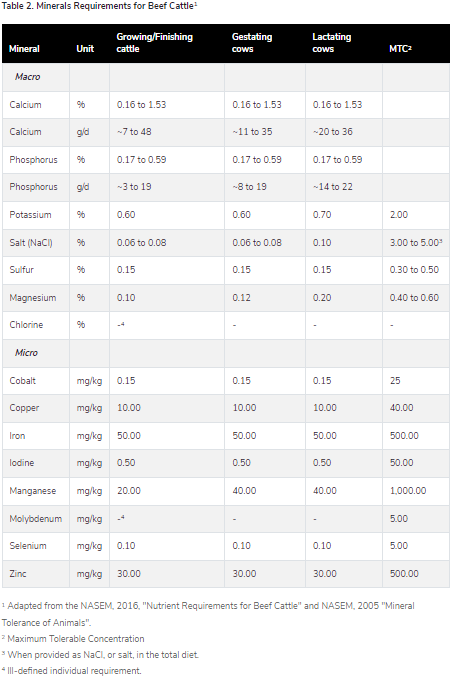

Requirements

Due to the critical functions of minerals in a number of body systems, there are specific mineral requirements for cattle. These requirements are often partitioned by class of cattle: growing, gestating, or lactating (Table 2). In addition, because minerals make up such a small proportion of the body and the diet, there are maximum tolerable concentrations (also in Table 2), or concentrations that if we exceed, cause toxicity problems and may risk doing more harm than good for the animal.

Calcium and phosphorus requirements are specified in grams per day and percent of the daily intake. The grams per day is specified because it is a more accurate representation of the animals' true needs; however, most feed labels will list percent Ca and P. Calcium and phosphorus function together within the body in a well-defined synchrony. The ratio of Ca to P in the total diet that cattle consume should be maintained close to a 2:1 ratio. The grams per day requirements are presented as fairly wide ranges. This is because Ca and P are critical for growth, thus, the more pounds per day cattle gain, the more grams per day of Ca and P will be required. Similarly, because Ca and P are excreted in the milk, the more milk the cow produces per day, the more grams of Ca and P she will require. As long as close to a 2:1 ratio of Ca to P is maintained, cattle can tolerate wide ranges in the supply of these two macro minerals. For brief periods of time, cattle can tolerate shifts outside of the 2:1 ratio, tolerating from 1:1 to 6:1 supplies of Ca:P. These ranges do not represent the ideal and should not be maintained long-term. The ratio of Ca:P assumes supply from the entire diet, so knowing concentrations of Ca and P in feedstuffs is helpful.

Perhaps the most challenging part about mineral requirements for cattle operations is that minerals are supplied not just through supplementation but through the daily feeds delivered or grazed. If animals graze, the soil mineral concentrations can impact their mineral requirements. Not only do soil mineral concentrations alter forage mineral concentrations but soils themselves are also consumed by grazing animals. Take the Ca:P ratio discussed above.

Grain sources tend to contain elevated concentrations of P, requiring additional Ca supplementation. Inversely, forages fed in cattle diets often contain adequate Ca but require additional P supplementation to balance the ratio. In the case of Ca and P, as long as the 2:1 ratio is maintained, cattle can function in a wide supply range of these minerals. For this reason, maximum tolerable concentrations are intentionally not specified for Ca and P. However, maximum tolerable concentrations can be critical for other minerals.

The maximum tolerable concentrations, sometimes referred to as MTL or maximum tolerable levels, are set based on animal health outcomes. That is, above these concentrations, abnormal cattle health outcomes could be expected. Many of the mineral toxicities and deficiencies occur among micro minerals. This is because these micro minerals are required in very minute amounts; therefore, there is a narrow range between what is required by cattle and what can become potentially dangerous to their health.

Always consult with your veterinarian or nutritionist when attempting to diagnose mineral deficiencies or toxicities.

Common mineral toxicities in cattle

Few macro minerals reach toxic concentrations, the exceptions are sulfur (S) and potassium (K). Elevated S in water sources is often the cause of sulfur toxicity, although some byproduct feeds can also contain elevated S concentrations. Cattle suffering from S toxicity may head press (push their heads into the corner or a pen) or stagger in the pen or pasture. These symptoms occur because the elevated S is impairing the neurological (brain) functions of those animals. In early spring pastures, K concentrations are elevated, causing a secondary deficiency of magnesium (described below).

Molybdenum (Mo) is considered an essential mineral, meaning this mineral is needed by cattle for normal body function; however, required concentrations are not even listed in many resources (note Table 2). This is because cattle operations are far more likely to deal with Mo in excess than to deal with deficiencies.

Most soils contain adequate concentrations of Mo to supply feedstuffs commonly fed to cattle and eliminate the need for supplemental Mo. Some soils, particularly soils fertilized with contaminated lime or biosolids, can accumulate Mo. This accumulation of Mo causes it to interfere with copper (Cu) and reduces the Cu absorption. Thus, Mo in excess often presents as a Cu deficiency (see below).

Selenium (Se) is a mineral with a VERY narrow range between required and toxic. Depending on the region of the country, cattle producers may deal with soils containing toxic concentrations or soils containing deficient concentrations of Se.

Knowing the concentration of Se in soils on a grazing operation should be the first step in diagnosing challenges. Severely toxic concentrations of Se in cattle will result in hair loss and damaged hooves.

Common mineral deficiencies in cattle

Similar to toxicities, macro minerals are rarely deficient in cattle. The one exception to that rule would be magnesium (Mg). Magnesium deficiency in cattle can be relatively common when cattle graze lush spring pastures. These pastures contain elevated potassium (K) which causes a secondary Mg deficiency. Supplements for cattle labeled as “HiMag” are common for this reason. These supplements often contain up to 10% Mg to supply adequate Mg during the early spring grazing season.

Copper (Cu) deficiencies in cattle may be caused by primary mechanisms, meaning not enough Cu was supplied to the animal, or secondary mechanisms, meaning adequate Cu should be in the diet, but something is interfering with its ability to be absorbed by the animal. Deficiency of Cu impairs reproductive and immune functions. Therefore, deficient cattle may have trouble becoming pregnant or maintaining a pregnancy, or cattle deficient in Cu may get sick more often.

In cases of minor deficiency, growth may just be slightly reduced such that one is not even aware of the deficiency. In other cases of prolonged deficiency, the hair coat of cattle changes color from the root outward. For example, black cattle develop an orange tinge to their hair coat, but not at the tips like sun-bleaching. This color change occurs at the roots.

Selenium deficiency often impacts newborn calves in a condition referred to as White Muscle Disease (WMD). Calves with WMD are weak are birth and often unable to stand and suckle. While this disorder can be reversed by using injectable Se, it is recommended cattle producers examine their herd mineral plan to ensure gestating cows have an adequate supply of Se. Like Cu, Se deficiency can also present more mildly with simply increased sickness and impaired male and female reproduction.

While other deficiencies and toxicities related to minerals certainly exist, cattle producers should regularly test feeds and soils to better understand these relationships and the potential risk to their own operations.

Examples of mineral tags or labels

Perhaps the most important thing producers can understand and appreciate is how to read a feed tag and pick the right minerals for cattle. For certain minerals, the requirements shift depending on the class of cattle being fed. Therefore, when purchasing a mineral, look for a tag that specifies the type of cattle that will be supplemented.

In the tables provided below, there are a few key things to keep in mind:

- These tables were formulated assuming cattle consume the given diet at roughly 2% of their body weight.

- These tables were drafted considering the average needs of cattle in each scenario. A reasonable range of concentrations exists in each scenario.

- Those elements NOT commonly supplemented in beef cattle diets were removed to reduce table size. They are still required elements, but not generally of concern in supplements.

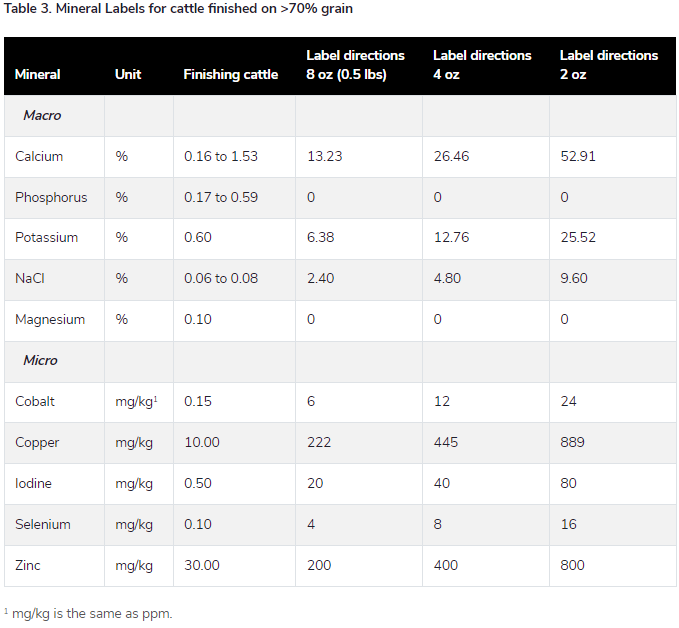

Example 1: Possible label considerations for finishing cattle consuming greater than 70% grain (dry matter basis)

Table 3 depicts possible tag labels for supplements formulated to be fed to cattle consuming a grain-based diet. In this scenario, one assumes that greater than 70% of the diet comes from corn grain. This is important because when looking for a mineral supplement that will balance the Ca:P at 2:1 when cattle consume grain, remember that grains supply excess P.

While cattle require a range of P on a grams per day basis, this often works out to about 0.15% of their dry matter intake. Corn grain contains 0.3% P by itself. Therefore, if the bulk of the dietary intake is corn grain, cattle requirements for P are typically met, but Ca is not. In fact, finding a mineral program that meets the Ca requirement of grain-fed cattle can be difficult. Generally, cattle consuming grain-based diets are fed a mineral pack that meets their other mineral requirements, and then CaCO3 (limestone) is supplemented to balance the Ca:P ratio. Using CaCo3 to supply Ca is the cheapest approach to balance Ca:P.

Thus, cattle producers looking to meet the needs of their grain-fed cattle are encouraged to consider the feeding directions and the amount of other minerals in the tag. Work with a nutritionist to determine how much limestone may need to be added to balance the calcium-to-phosphorus ratio in the diet.

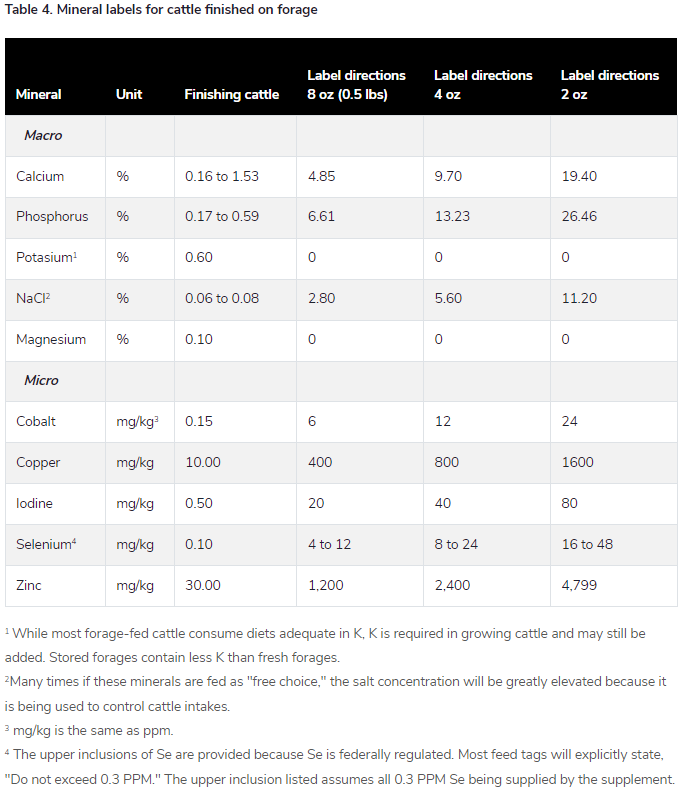

Example 2. Possible label considerations for cattle fed predominantly forage

The challenge with considering possible mineral labels for forage-fed cattle is not knowing the soil or forage composition to determine the supply of minerals from the diet of the cattle. For example, one can calculate needs based on book values for Orchard grass hay, but this is a very dangerous assumption. Therefore, what far more mineral supplementation programs rely on is meeting the needs of the animals without knowing what will be supplied by the diet. Table 4 then presents possible mineral tags that may be generally formulated for growing and finishing cattle.

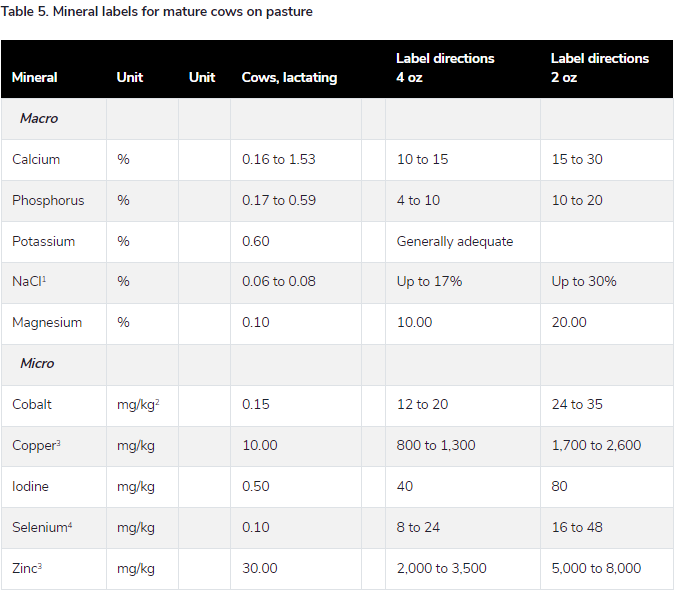

Example 3: Possible label considerations for mature, grazing cows

Finally, cows fed forages have slightly altered requirements when compared to growing and finishing cattle. While the book values acknowledge the difference between requirements for cows in gestation and cows in lactation, rarely can we find mineral supplements specific to these classes of cattle. That makes sense because typically we feed an entire herd of cows and may have cows both in lactation and gestation simultaneously. Therefore, in Table 5 below, only lactation requirements are presented because they represent the upper range and will be the basis for most supplements. Keep in mind that just as in our forage finished cattle in Table 4, many of the macro mineral needs are met.

In Table 5, magnesium is also included to offset any elevated potassium. While most producers may select to feed a "HiMag" mineral only in the spring, it can be fed year-round and may be advantageous if wet forages, such as baleage, provide the bulk of winter cow feed.

Summary

The best way to determine the mineral needs of a beef cattle operation is to determine the mineral concentrations in the feedstuffs or the pastures cattle consume. Choose a mineral supplementation program that will best match the needs of the feeding system. Most mineral companies are happy to assist in an exploratory process to analyze samples and find a program best suited to the operation. To learn more about determining the mineral needs for a beef cattle operation, speak with a nutritionist or extension specialist.