Lumpy skin disease: Epidemiology

Learn more about cause and transmission of lumpy skin diseasePart of Series:

Next Article in Series >

Editors note: The following content is an excerpt from Lumpy Skin Disease: a field manual for veterinarians which is designed to enhance awareness of lumpy skin disease and to provide guidance on early detection and diagnosis for private and official veterinary professionals (in the field and in slaughterhouses), veterinary paraprofessionals and laboratory diagnosticians.

Lumpy skin disease is a vector-borne pox disease of domestic cattle and Asian water buffalo and is characterized by the appearance of skin nodules. Endemic across Africa and the Middle East, the disease has, since 2015, spread into the Balkans, the Caucasus and the southern Russian Federation. Outbreaks of LSD cause substantial economic losses in affected countries, but while all stakeholders in the cattle industry suffer income losses, poor, small-scale, and backyard farmers are hit hardest. The disease impacts heavily on cattle production, milk yields, and animal body condition. It causes damage to hides, abortion, and infertility. Total or partial stamping-out costs add to direct losses. Indirect losses stem from restrictions on cattle movements and trade.

In addition to vectors, transmission may occur through consumption of contaminated feed or water, direct contact, natural mating or artificial insemination. Large-scale vaccination is the most effective way of limiting the spread of the disease. Effective vaccines against LSD exist and the sooner they are used the less severe the economic impact of an outbreak is likely to be.

Epidemiology

Typically, LSD outbreaks occur in epidemics several years apart. The existence of a specific reservoir for the virus is not known, nor is how and where the virus survives between epidemics. Outbreaks are usually seasonal but may occur at any time because in many affected regions no season is completely vector-free.

Presence of growing numbers of naïve (i.e. not immune) animals, abundance of active blood-feeding vectors, and uncontrolled animal movements are usually drivers for extensive LSD outbreaks. The primary case is usually associated with the introduction of new animal(s) into, or in close proximity to, a herd.

Morbidity varies between 2 and 45 percent and the mortality rate is usually less than 10 percent. Susceptibility of the host depends on immune status, age, and breed. Generally speaking, high milk-producing European cattle breeds are highly susceptible compared to

indigenous African and Asian animals. Cows with high milk production are usually most severely affected.

Asymptomatic, viraemic cattle are commonly detected among infected animals, experimentally and in the field. In order to stop the disease from spreading, it is therefore essential to consider the possible presence in an affected herd of infected animals showing no visible clinical signs, as such animals are capable of transmitting the virus via blood-feeding vectors. The movement of unvaccinated/not immune cattle from infected regions poses a major risk of contagion.

CAUSATIVE AGENT

Lumpy skin disease is caused by the lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV), a member of the genus Capripoxvirus (CaPV) within the family Poxviridae. Lumpy skin disease virus shares the genus with sheep pox virus (SPPV) and goat pox virus (GTPV), which are closely related, but phylogenetically distinct. There is only one serological type of LSDV, and LSD, SPP and GTP viruses cross-react serologically. The large, double-stranded DNA virus is very stable, and very little genetic variability occurs. Therefore, for LSDV, farm-to-farm spread cannot be followed by sequencing the virus isolates, as is done with other TADs, e.g. foot-and-mouth disease (FMD).

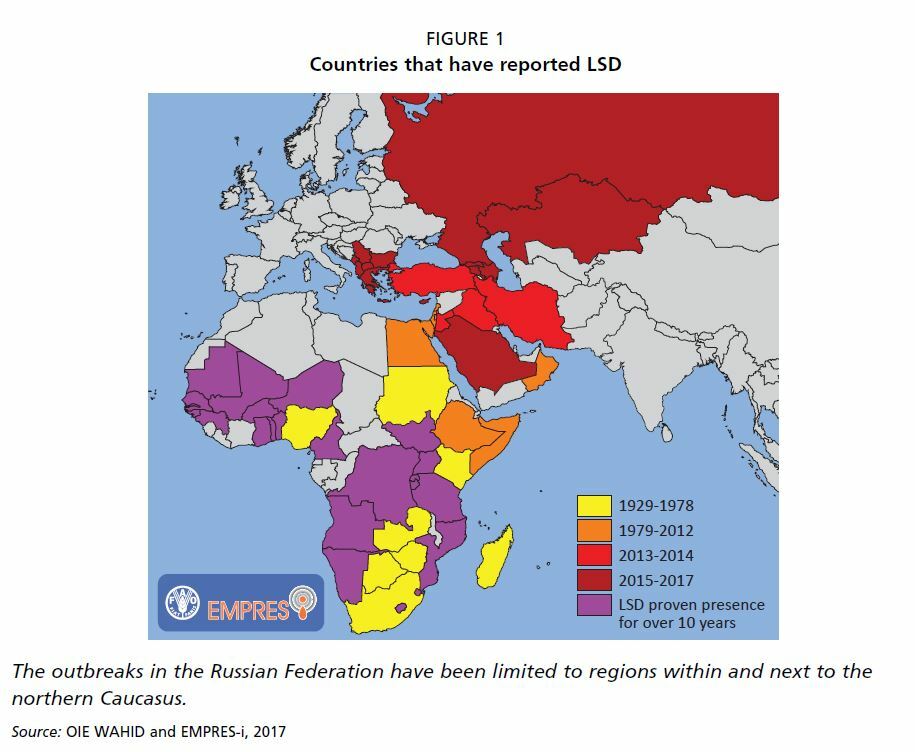

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION

Lumpy skin disease is widespread and endemic throughout Africa, excluding Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Libya. Since 2013, LSD has swept throughout the Middle East (Israel, the Palestinian Autonomous Territories, Jordan, Lebanon, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Oman, Yemen, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain). In 2013, LSD also spread to Turkey, where it is currently endemic. This was followed by outbreaks in Azerbaijan (2014), Armenia (2015) and Kazakhstan (2015), the southern Russian Federation (Dagestan, Chechnya, Krasnodar Kray and Kalmykia) and Georgia (2016). Since 2014, LSD has advanced into the northern part of Cyprus, Greece (2015), Bulgaria, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania and Kosovo (2016). Currently there is an increased risk of LSD reaching Central Asia, Western Europe and Central-Eastern Europe.

SUSCEPTIBLE HOSTS

Lumpy skin disease is host-specific, causing natural infection in cattle and Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), although the morbidity rate is significantly lower in buffalo (1.6 percent) than in cattle (30.8 percent) (El-Nahas et al., 2011). Some LSDV strains may replicate in sheep and goats. Although mixed herds of cattle, sheep and goats are common, to date no epidemiological evidence on the role of small ruminants as a reservoir for LSDV has been reported. Clinical signs of LSD have been demonstrated after experimental infection in impala (Aepyceros melampus) and giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). The disease has also been reported in an Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) and springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis). The susceptibility of wild ruminants or their possible role in the epidemiology of LSD is not known. Lumpy skin disease does not affect humans.

TRANSMISSION

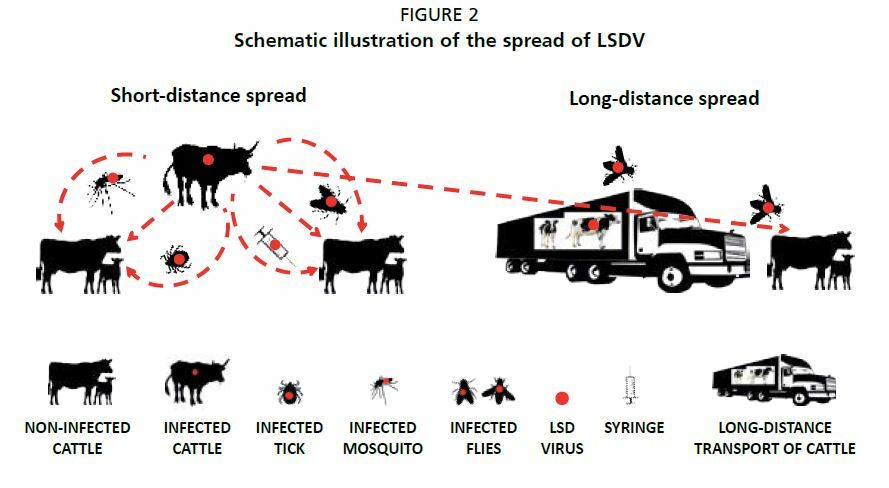

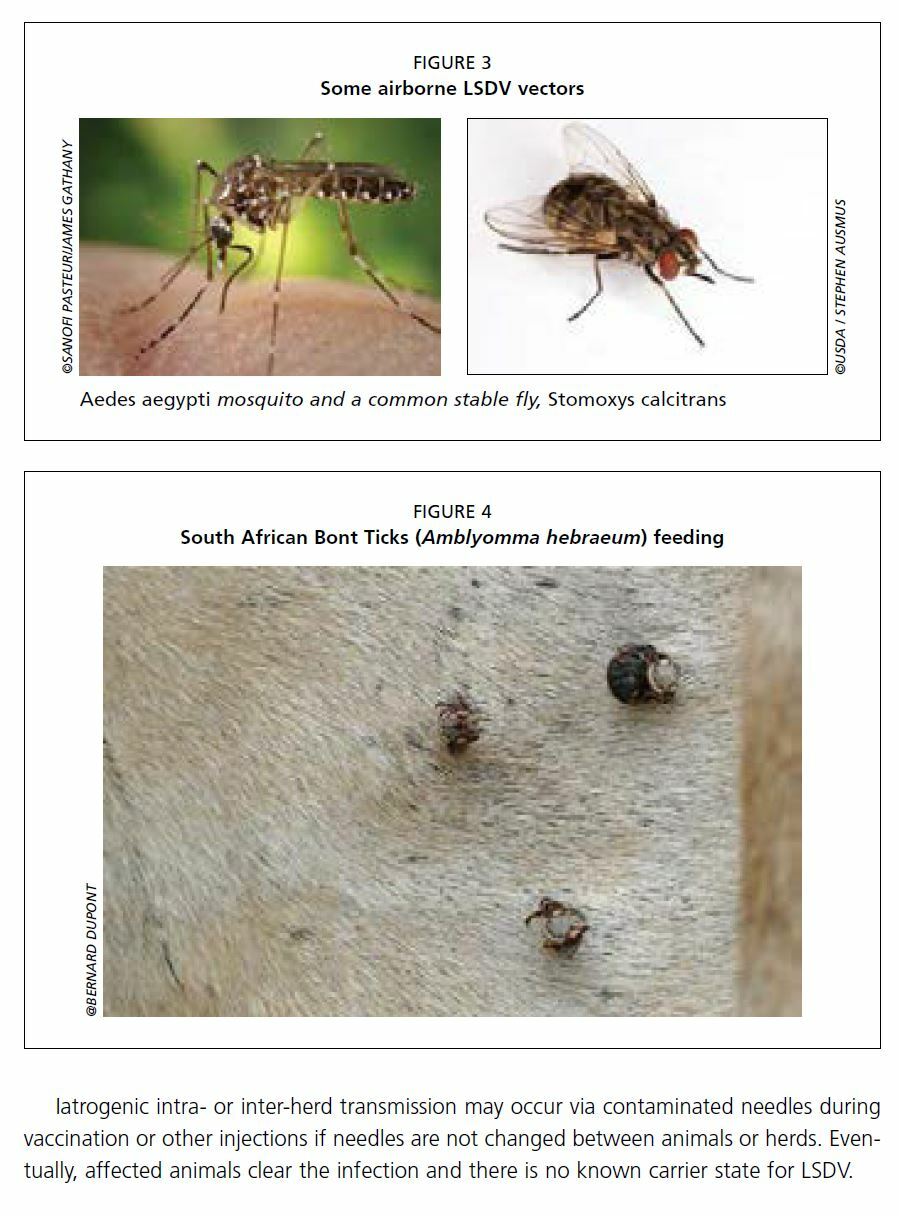

The first case of LSD can often be traced to the legal or illegal transfer of cattle between farms, regions or even countries. In fact, movements of cattle may allow the virus to jump over long distances. Short-distance leaps, equivalent to how far insects can fly (usually < 50 km), are occasioned by numerous local blood-feeding insect vectors feeding on cattle and changing hosts frequently between feeds. No evidence exists of multiplication of the virus in vectors, but it cannot be excluded. The principal vector is likely to vary between geographical regions and ecosystems. The common stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans), the Aedes aegypti mosquito, and some African tick species of the Rhipicephalus and Amblyomma spp., have demonstrated ability to spread the LSDV. Viral transmission from infected carcasses to naïve live animals via insects is a possible risk, but has not been sufficiently studied.

Direct contact is considered ineffective as a source of infection, but may occur. Infected animals may be viraemic only for a few days, but in severe cases viraemia may last for up to two weeks. Infected animals showing lesions in the skin and mucous membranes of the mouth and nasal cavities excrete infectious LSDV in saliva, as well as in nasal and ocular discharges, which may contaminate shared feeding and drinking sites. To date, infectious LSDV has been detected in saliva and nasal discharge for up to 18 days postinfection. More research is needed to investigate how long the infectious virus is excreted in such discharge.

Infectious LSDV remains well-protected inside crusts, particularly when these drop off from the skin lesions. Although no experimental data are available, it is likely that the natural or farm environments remain contaminated for a long time without thorough cleaning and disinfection. Field experience shows that when naïve cattle are introduced to LSDV-infected holdings after stamping out, they become infected within a week or two – indicating that the virus persists either in vectors, the environment, or both.

The virus persists in the semen of infected bulls so that natural mating or artificial insemination may be a source of infection for females. Infected pregnant cows are known to deliver calves with skin lesions. The virus may be transmitted to suckling calves through infected milk, or from skin lesions in the teats.

Reference:

Tuppurainen, E., Alexandrov, T. & Beltrán-Alcrudo, D. 2017. Lumpy skin disease field manual – A manual for veterinarians. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 20. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 60 pages.

Headline image courtesy of ©BFSA/Tsviatko Alexandrov