Foot-and-mouth disease SOPs: Overview of ecology

Learn more about which species are most susceptible to FMDVEditor's note: The following content is an excerpt from Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP): Foot-and-Mouth Disease Standard Operating Procedures: Overview of Etiology and Ecology which is designed to provide operational guidance for responding to an animal health emergency in the US.

FMD is currently endemic in areas of Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and South America. Seven of these countries maintain FMD OIE-endorsed control programs: China, India, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Morocco, Namibia, and Thailand. Only 68 countries, including those of North America (the United States, Canada, and Mexico), Central America, and Western Europe, as well as Australia and New Zealand are free of FMD (without vaccination). The last FMD outbreak in the United States was in 1929.

Susceptible species

FMDV infects cloven-hooved mammals (order Artiodactyla), as well as a few species in other orders. Livestock susceptible to FMD, common in the United States, include:

- cattle

- pigs

- sheep

- goats

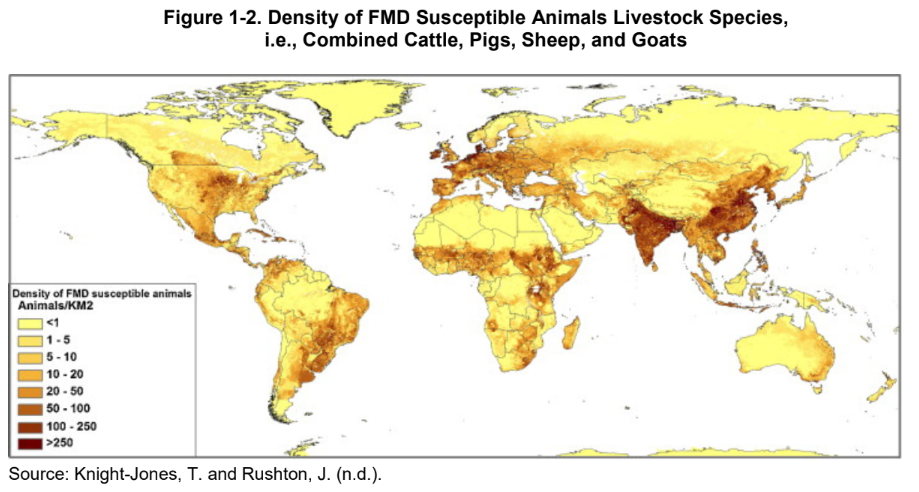

In addition, deer, bison, and elk are also susceptible to the virus. Wild pigs, antelope, African buffalo, Bactrian camels, elephants and giraffe are also all susceptible species. Llamas and alpacas have been infected experimentally, but do not seem to be highly susceptible to natural infection. Other animals like rats, mice, guinea pigs, and armadillos have all been experimentally infected. Strains may have a predilection for one animal species over another. For example, serotype O, Cathay topotype, causes severe disease in pigs, but not in cattle. Figure 1-2 presents the density of FMD susceptible livestock species in the world.

Carrier state

A carrier is defined as an animal in which there is persistence of FMDV or the viral genome in the pharyngeal region for at least 28 days post-infection. Generally speaking, a “carrier” is defined in epidemiological terms as an animal that is infected and can disseminate the infection in the absence of symptoms. This is to be distinguished from animals with neoteric infections, or subclinical infections of hosts immune from fulminant disease, e.g., vaccinated animals.

Animals with neoteric infections may shed large amounts of virus; however, with FMD, carrier animals shed low amounts of virus and may or may not be able to transmit infection in field conditions. African buffalo are the only carrier animals that have been demonstrated to be able to definitively transmit FMDV (SAT serotypes) to other buffalo and potentially cattle. For more information on carrier transmission, please see the FAD PReP/NAHEMS Guidelines: Vaccination for Contagious Diseases, Appendix A: FMD found at www.aphis.usda.gov/fadprep.

In addition to African buffalo, water buffalo, cattle, sheep, and goats can also become carriers. The duration of the carrier state in farm animals has been reported to be as long as 3.5 years for cattle and 9 months for small ruminants. Commonly, studies indicate that greater than 50% of infected cattle may still harbor FMD virus 6 weeks to 6 months after initial infection, clearing within 2 years. Persistent infections have also been identified in some experimentally infected wildlife species, including white-tailed deer and kudu, but not feral swine.

There has been no carrier state identified in swine. Pigs clear FMDV from sera, oral, nasal or oropharyngeal fluids in 28 days, although FMDV RNA could be extracted from lymph node tissue at 60 days post-infection.

The epidemiological significance of carrier animals in FMD outbreaks of cattle is uncertain. Although there is no evidence that any carrier species can transmit FMDV in the field to naïve animals, the perception of risk remains and cannot be discounted. The prevalence of carrier animals in a herd and factors influencing this prevalence—regardless of whether vaccination is employed—continues to require additional research. The NAHEMS Guidelines: Vaccination for Contagious Diseases, Appendix A: FMD contains more information on the known epidemiological role and prevalence of carrier animals, impact of vaccination on carrier status, and detection of carriers via diagnostic testing.

Introduction and transmission of FMDV

FMD is highly contagious. FMDV is typically introduced via contact with infected animals, their secretions, excretions, or fomites, or products contaminated with FMDV. FMD can also be introduced into a naïve animal population by feeding contaminated meat, milk, or garbage. Conveyances may be responsible for transmitting the disease between an infected and an uninfected premises. Insects and birds may also be mechanical vectors; no biological vector of the virus has been identified. Cattle typically become infected through aerosolized virus. Pigs usually become infected by eating virus-contaminated food, or through direct contact with the vesicular lesions of other animals. Pigs also can excrete large quantities of the virus through respiration, infecting susceptible animals. As such, pigs are considered key amplifiers of the virus.

Live animals and virus shedding

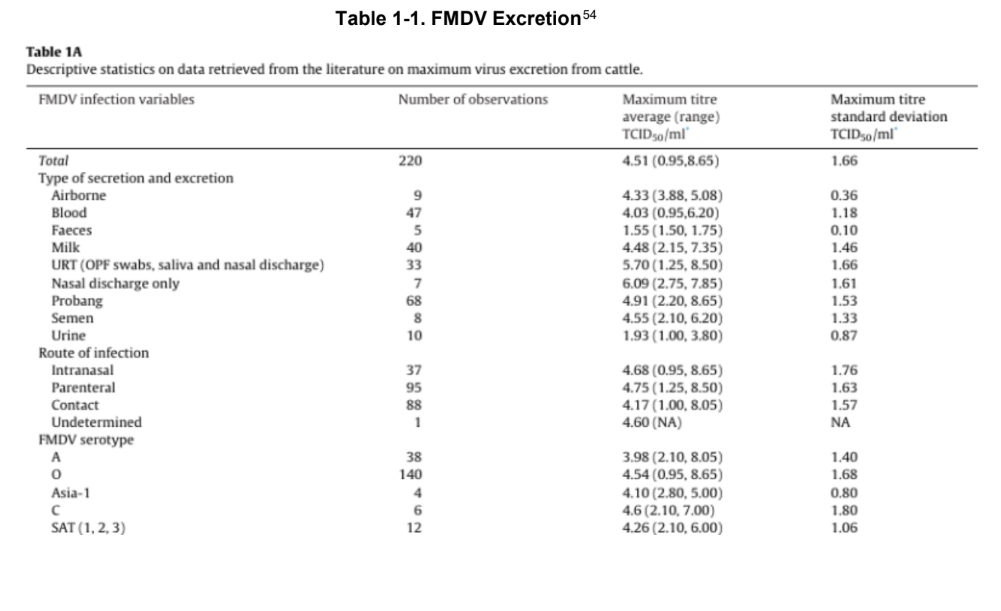

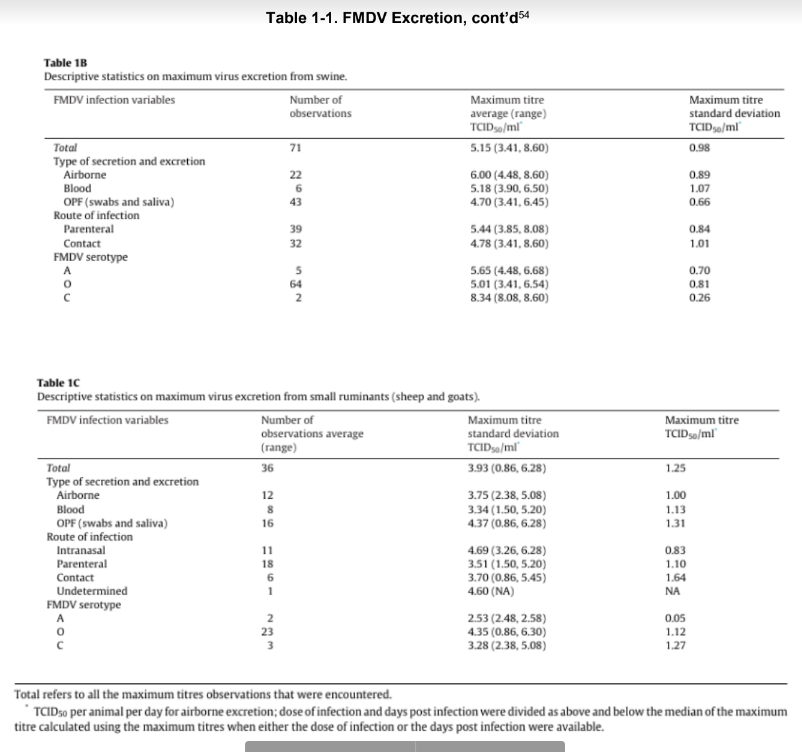

Animal to animal contact is a common mode of transmission. FMDV is shed in all secretions and excretions, including saliva, milk, semen, and ruptured vesicular fluid, and to a lesser extent, feces and urine. Pigs produce nearly 3,000-fold more of FMDV in respiratory secretions than either cattle or sheep. The amount of virus excreted by various species will also vary based on the serotype and strain of the FMDV. Table 1-1 provides the approximate amount of virus excretion for cattle, pigs, and small ruminants, respectively in A, B, and C, indicating the significant difference in their levels of virus shedding.

Because cattle are more likely to be infected through inhalation, and pigs shed a significant amount of FMDV via respiration, highly concentrated herds of infected pigs in close proximity to naïve cattle herds poses a significant risk of transmission from pigs to cattle.

Air/Windborne transmission

Airborne FMDV can result from a large number of infected pigs, resulting in plumes of aerosolized virus in the atmosphere.

Cattle, because they inhale more air and are easily infected through respiration, are the species frequently infected when FMDV is airborne. Under specific climate conditions (particularly downwind), aerosolized FMDV produced by infected pigs can travel a significant distance often infecting cattle from upwards of 10 kilometers (km)—20-300 km being predicted with simulation models in the United Kingdom, and infecting sheep from 10–100 km away.

Many different factors influence how well FMD aerosolizes, and how far aerosolized virus may spread. As already mentioned, the species of the infected animal is significant, as pigs excrete more virus through respiration than cattle or sheep. In addition, the amount of virus emitted into the air will be impacted by the stage of the disease in the infected animal, as well as the number and concentration of infected animals, and the strain of the virus.

In terms of climatic conditions, a relative humidity of percent or more, with low and steady winds, is favorable for FMDV spread via aerosol. The virus also seems to spread significantly better over water than over land.

Fomite transmission

FMDV is readily transmitted through vehicles, equipment, boots, clothing, and other fomites. In an FMD outbreak, the movement of fomites is a critical transmission pathway which must be addressed, particularly because FMDV can persist on fomites for an extended period of time with persistence based on many factors, including decreased temperatures.

Personnel

One experimental study demonstrated that humans can harbor FMDV in their nasal passages for 28 hours (one subject), although the concentration of virus was markedly reduced over the first 3.5 hours post-exposure and below the assay limit of detection in 24 hours in the other subjects. Under experimental conditions, personnel carrying the virus in this manner were able to transmit infection to naïve animals.

For this reason, responders may be advised by regulatory officials to

employ a waiting period when traveling between premises. Evidence suggests that with appropriate biosecurity and cleaning and disinfection measures, the necessity for extended personnel waiting times or down periods is lessened.

Wildlife

It is unclear what role wildlife would play in disease transmission if there was an FMD outbreak in the United States, Red, fallow, and roe deer were all susceptible to FMDV when exposed in the laboratory, though severity of clinical signs varied.69 However, in the 2001 epidemic in the United Kingdom, evidence suggests deer were not epidemiologically important in the spread of FMD. A general conclusion is that wildlife would not likely play a role in transmission of FMDV to livestock in a U.S. FMD outbreak, with acknowledgement that propagation of disease by wildlife should be a consideration in a response effort.

Incubation period

The incubation period for FMD is typically 2–14 days, and is defined by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) as 14 days for the purpose of the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code (2019). During the beginning phases in the prevalence of FMDV, the incubation period may be as short as 24 hours. How fast clinical signs appear depends on the dose of the virus, species of the animal, as well as the route of infection. Animals may shed FMDV before the appearance of clinical signs.

Infectious dose

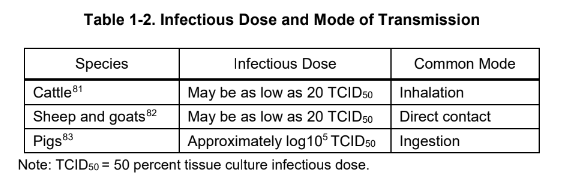

Different animal species vary in their susceptibility to FMDV, which is also influenced by the route of infection. Table 1-2 lists the infectious dose and mode of infection for key animals, given the primary mode of transmission for that species.

Morbidity and mortality

The morbidity and mortality of FMD varies depending on the species affected, as well as the serotype and strain of the virus. Morbidity is significant, and can approach 100 percent. Mortality is typically low in adult animals (1 to 5 percent), though higher mortality rates are typically observed in very young animals, usually from acute myocarditis.

Clinical signs

FMDV is typically characterized by high morbidity, evidenced by characteristic vesicles on the oral and nasal mucosa, teats, coronary bands, and interdigital spaces. However, before vesicles appear, a decreased appetite progresses as fever develops. The clinical signs can vary based on the serotype and strain of the FMDV. Generally speaking, sheep and goats typically have milder clinical signs than cattle. The following sections provide more detail on the clinical signs in cattle, pigs, and sheep and goats.

Cattle

Cattle usually present with fever, anorexia, shivering, and reduction in milk production for approximately 2–3 days, before vesicular lesions are observable on mucous membranes, interdigital spaces, and on the coronary band. The vesicles will rupture in approximately 1 day, and recovery occurs in 8–15 days. Excessive salivation is often observed in cattle and milk yields are reduced by 80 percent.

Pigs

In pigs, severe lesions typically are observed on the feet, as well as on the snout, udder, as well as hock and elbow. Excessive salivation is less likely in pigs than in cattle, and lesions in the mouth are milder than those observed elsewhere.

Sheep and goats

Fewer clinical signs are seen in sheep and goats. Mouth lesions are often not obvious, though lesions can develop on heel bulbs and on the coronary band. Sheep and goats may be important in transmission, as infection presents with mild clinical signs and may not be as immediately recognized.