Morocco - a top fertiliser producer - could hold a key to the world’s food supply

Morocco has a large fertiliser industry with huge production capacity and international reach. It is one of the world’s top four fertiliser exporters following Russia, China and Canada.

Morocco has a large fertiliser industry with huge production capacity and international reach. It is one of the world’s top four fertiliser exporters following Russia, China and Canada.

Fertilisers tend to divide into three main categories; nitrogen fertilisers, phosphorus fertilisers, potassium fertilisers. In 2020 the fertiliser market size was about US$190 billion.

Morocco has a distinct advantage in the production of phosphorus fertilisers. It possesses over 70% of the world’s phosphate rock reserves, from which the phosphorus used in fertilisers is derived. And this makes Morocco a gatekeeper of global food supply chains because all food crops require the element phosphorus to grow. Indeed, so does all plant life. Unlike other finite resources, such as fossil fuels, there is no alternative to phosphorus.

In 2021, the global phosphorus fertiliser market amounted to about US$59 billion. In Morocco, the sector’s 2020 revenues amounted to US$5.94 billion. Office Chérifien des Phosphates, the producer owned by the Moroccan state, accounted for about 20% of the kingdom’s export revenues. It is also the country’s largest employer, providing jobs for 21,000 people.

Morocco plans to produce an additional 8.2 million tonnes of phosphorus fertiliser by 2026. Currently production is at about 12 million tonnes.

The state company recently announced that it would increase its fertiliser production for the year by 10%. This would put an additional 1.2 million tonnes on the global market by the end of the year. This will significantly help markets.

But, as I argue in a new report, Morocco faces new challenges. Its production of fertiliser is threatened by increasingly daunting environmental and economic challenges. They include the COVID pandemic and the severe supply chain disruptions that have followed.

The timing to address these is crucial.

Russia is currently the world’s largest fertiliser exporter – 15.1% of total exported fertilisers. And fertiliser represents one of the greatest vulnerabilities for both Europe and Africa. For instance, the EU27 (all of the 27 member state of the European Union) as a whole depends on Russia for 30% of its fertiliser supply. Russia’s advantageous position is amplified by its status as the world’s second-largest natural gas producer. Gas is a main component of all phosphorus fertilisers as well as nitrogen fertilisers.

Because of this, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has serious implications for global food security. Both in terms of supply, and also because fertiliser can be used a economic weapon or tool.

Morocco could therefore become central to the global fertiliser market and a gatekeeper of the world’s food supply that could offset the attempt to use fertiliser as a weapon.

The journey

Morocco started to mine phosphorous in 1921. During the 1980s and 1990s it began to produce its own fertiliser. Office Chérifien des Phosphates built the world’s largest fertiliser production hub in Jorf Lasfar on Morocco’s Atlantic coast.

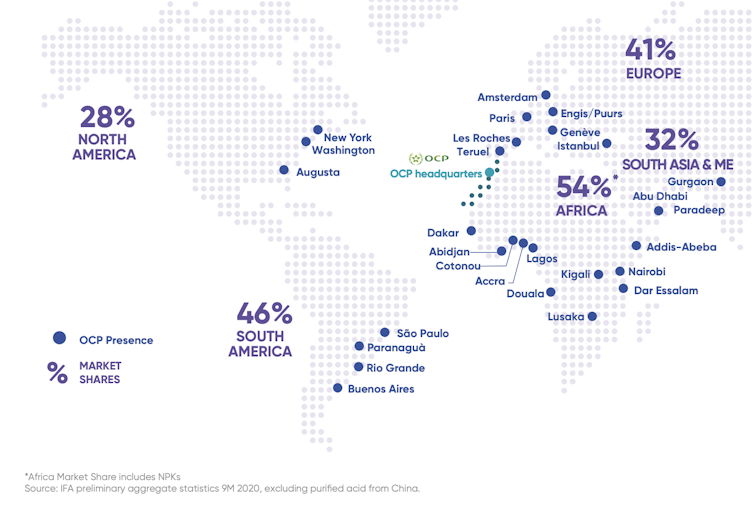

Before the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, the company had over 350 clients on five continents. About 54% of phosphate fertilisers bought in Africa come from Morocco. Moroccan fertilisers also account for major domestic market shares in India (50%), Brazil (40%) and Europe (41%). India and Brazil have reached out to Morocco to fill additional supply gaps.

Morocco’s economy has reaped the benefits of the transformation into an international fertiliser exporting giant. And in sub-Saharan Africa in particular, the combination of joint venture partnerships in local fertiliser production and direct outreach to farmers has resulted in a remarkable boost to African agricultural yields.

It’s also expanded Morocco’s soft power influence across the continent. For instance, Morocco supplies over 90% of Nigeria’s annual fertiliser demand.

But, how well Morocco manages challenges to the industry will affect both its own economic development and the stability of food supplies across the world.

The challenges

Water and energy constraints

Phosphate extraction and fertiliser production uses a lot of energy and water. Morocco’s phosphate and fertiliser industry consumes about 7% of its annual energy output and 1% of its water.

But Morocco is among the countries suffering the most from water scarcity. This is due to a dry climate, high water demand, climate change and reservoir contamination and siltation.

Morocco is trying to address this through a National Water Plan 2020-2050. It envisages building new dams and desalination plants and expanding irrigation networks, among other measures, to sustain agriculture and ecosystems. It’s estimated to cost about US$40 billion.

Natural gas costs

Nitrogen is the other basic fertiliser element that plants need. Diammonium phosphate, the most popular type of phosphorus fertiliser worldwide (and which Morocco makes along with monoammonium), is composed of 46% phosphorus and 18% nitrogen. Natural gas accounts for at least 80% of the variable cost of nitrogen fertiliser.

This means the price of natural gas massively affects production costs. But Morocco has scant natural gas resources. And natural gas prices have been soaring.

How well Morocco manages the food-water-energy nexus will affect both its own economic development and the stability of food supplies across the world.

Some answers

The key is to expand its renewable energy sector. Morocco holds considerable solar and wind resources. Fertiliser manufacturing could become powered by renewable energy, and renewable energy could be used within the fertiliser itself.

In 2020, the state’s fertiliser company covered 89% of its energy needs by co-generation (producing two or more forms of energy from a single fuel source) and renewable energy sources. Its aim is to eventually cover 100% of its energy needs in this way.

Renewable energy could also be used within the fertiliser itself. Instead of importing ammonia derived from natural gas, Morocco could produce its own using hydrogen produced from its domestic renewable energy resources.

According to the state company, 31% of its water needs are met with “unconventional” water resources, including treated wastewater and desalinated seawater.

Morocco’s growing reliance on desalination plants to satisfy industrial, agricultural and residential needs will require sizeable new investments in power generation from renewable energy sources. Desalination plants require 10 times the amount of energy to produce the same volume of water as conventional surface water treatment.

To sustain operations and expand green ammonia production, Morocco will have to strike a careful balance between its fertiliser exports, its drive to expand its high-value agricultural exports and the provision of drinking water to its population.

Using its large solar energy resources to power green hydrogen and green ammonia production, along with desalination, Morocco could escape the vicious cycle of the upward spiralling of prices in the food-energy-water nexus.

Michaël Tanchum, Senior Fellow at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Studies (AIES), non-resident fellow in the Economics and Energy Program at the Middle East Institute (MEI) and Professor, Universidad de Navarra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The article was posted July 2022.