Pinkeye in Cattle: Treatment, Prevention and Control

Medical solutions are available for Pinkeye, but management can stop the condition becoming a problem on your farm, says the Mississippi State Extension Service.Pinkeye is an acute, contagious ocular disease of cattle that occurs worldwide. While cattle of all ages can be affected, calves get more severe infections.

Affected animals will develop runny eyes and conjunctivitis. Pinkeye causes sensitivity to light, so affected animals will squint and seek shaded areas for relief.

One or both eyes may be affected, and the signs of disease can last up to several weeks. Severe infections can cause corneal ulcers and scarring.

Severe scarring may result in blindness. According to the USDA APHIS National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) Beef 1997 report, pinkeye was the most common cause of illness in all breeding females and the second most common cause of illness in calves more than 3 weeks old.

The U.S. beef industry loses about $150 million annually to pinkeye. Pinkeye can be costly because of treatment costs (including labor and antibiotic costs), reduced value of animals with scarred or 'blue' eyes, and possibly reduced weaning weights of calves. Animals suffering from pinkeye may have decreased appetite because of pain or decreased vision that results in an inability to locate food and water.

Causes of Pinkeye

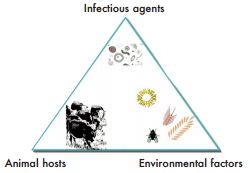

Many factors contribute to the development of pinkeye. Infectious agent factors, environmental factors, and animal factors must all be considered when examining the cause of pinkeye in cattle. The bacterium Moraxella bovis (M. bovis) is the main infectious cause of pinkeye in cattle.

The surface of this bacterium is covered in hair-like structures called pili, which allow it to attach to the surface of the cornea and avoid being rinsed away through normal tearing. The organism can be found in both ocular and nasal secretions of infected cattle.

Other organisms that may contribute to the disease include Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR). The infectious organism can be transmitted through direct contact with other infected animals, flies, and inanimate objects, such as instruments and halters. Irritants, such as excessive sunlight, dust, grasses, pollens, and flies, may predispose or worsen the disease in your herd. Flies can irritate and inflame the eye, making infection more likely.

Furthermore, flies can transmit M. bovis as they feed on the eye secretions of affected animals. Cattle may also irritate their eyes when they eat hay out of the middle of a round bale or from overhead feeders. Breeds that lack pigment around the eye, such as Hereford and Charolais cattle, may be especially sensitive to UV light and predisposed to ocular inflammation. Studies have shown that Brahman or Brahman-influenced cattle tend to resist the disease.

Treatment of Pinkeye

Treating pinkeye early is key to eliminating the causative organism and reducing the likelihood that it will be passed from animal to animal. In studies, the M. bovis organism is sensitive to oxytetracycline and penicillin.

Long-acting oxytetracycline injections have been shown to be effective when used early. When large numbers of animals are affected, oxytetracycline injections are often used in combination with medicated tetracycline feeds. Penicillin injections under the conjunctiva, or thin membrane of the eye, have also been shown to be very effective but are more labor intensive and require better restraint.

If you are seeing a large number of pinkeye cases that are resistant to treatment, contact your herd veterinarian. Other organisms may be involved in the disease, or altered antimicrobial sensitivity patterns may exist, and a veterinarian can determine specific antimicrobial sensitivity patterns for the infectious organism in your herd.

It is important to follow the labeled dose and route of administration of the product you are using. Many of the nitrofuracin sprays and puffers that were used years ago are now illegal to use in cattle.

Approved sprays and ointments may be quite effective but must be applied several times a day. Spraying from a distance is usually ineffective because the animals will blink or turn when approached.

Using an eye patch or other material to cover the eye may help protect the eye from further irritation and decrease the spread of the organism.

When severe corneal ulcers exist, your veterinarian can perform a third eyelid flap or suture the eyelids closed to protect the eye.

When you examine an animal with pinkeye, be sure to use a new pair of disposable gloves for each animal to reduce transmission from animal to animal. Disinfect any equipment, such as halters or nose tongs, that may touch infected secretions. If possible, isolate infected animals to decrease the potential for disease transmission.

Prevention and Control of Pinkeye

Fly control is an essential part of treating and preventing pinkeye. Current methods of fly control include insecticidal ear tags, sprays, pour-ons and charged backrubbers. Environmental insecticide programs, such as feed additives that target the larvae in the manure, are also available. The two main types of insecticidal ear tags are organophosphates and pyrethroids.

Alternate the type of tag used every year to reduce the likelihood of flies developing resistance. Remove tags at the end of the fly season, usually in late November in the southeastern United States. Keeping pasture cut and free of seedheads is an important part of control because small cuts or abrasions on the eye can allow the infectious organism to enter.

Spread hay out and avoid or lower overhead feeders if possible. Prevent overcrowding at the feed bunk and provide enough shade. Consider breeding for eyelid pigmentation, or consider introducing Brahman-influenced genetics if pinkeye is a severe problem in your area. Adult cattle can become immune to pinkeye following infection.

Commercial and autogenous vaccines are also available against M. bovis. These vaccine products protect inconsistently, and results vary from poor to excellent control of pinkeye. Check with your veterinarian to help you decide whether these products may be beneficial in your area. Because of the many factors that predispose an animal to pinkeye, no one single management practice can prevent and control the disease.

The higher incidence of pinkeye that we see in the late summer or early fall corresponds to the increase in flies, plant growth, pollen production, and hay feeding that is occurring in the animal's environment. By understanding and managing these risk factors, you can prevent or reduce the incidence of pinkeye in your herds.