Effect Of Heating On Feed Value Of Hay

Hay fires have been a major problem in south-east Australia in recent years. Hundreds of hay shed fires have been recorded in NSW, Victoria and South Australia due to spontaneous combustion. It is also likely that a significant amount of hay has been damaged by heating even though it did not ignite. Australian researchers look at what effect heating may have had on the feed value of hay.Introduction

A variety of factors are believed to influence hay heating and the risk of spontaneous combustion. These include moisture (or dry matter) content of the forage, crop or pasture species, air temperature and humidity, bale size, compaction and stacking. Other factors can also contribute to increased risk of hay heating and fire including variation in plant water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) levels and types, along with changes in waxy leaf cuticle (surface) due to moisture stress, uneven drying due to uneven crops, weeds or machinery used.

Risk of heating is affected by bale size, density and how it is stored. Smaller bales have a relatively large surface area, so can dissipate heat. Under dry conditions hay in small bales and lower density round bales will continue to lose some moisture after baling. However, once stacked in a shed the effective size of the lot increases and the comparative advantage of smaller bales to dissipate heat is lost.

As a general guide, hay which is baled at more than 20 per cent moisture is at risk of heating or going mouldy which will affect nutritional quality of the feed. If hay is baled at 25 to 35 per cent moisture (75 to 65 per cent dry matter), then spontaneous combustion is likely to occur.

Large rectangular or round bales retain more of the heat generated than small bales and are more likely to heat at lower moisture levels. Heat damage appears as brown or charred hay in the middle of the bale. When making large bales it is important to bale hay at a moisture content no higher than 14 to 16 per cent.

(Hay producers should check the recommended baling moisture for their baler with their machinery supplier). There is a very narrow range of moisture levels suitable for making large bale hay. If the forage is baled too wet it will heat. If it is baled too dry, leaf shatter and field losses during baling increase and can exceed 25 per cent if the hay is less than 12 per cent moisture.

Bale stacking configuration will also affect heat build-up. Tightly stacked square (rectangular) bales will not allow air movement and heat will build up. Some arrangements of round bales may allow heat to dissipate out of the stack (however damage is still possible in the middle of the bale).

What temperatures can heated hay reach?

An experiment was conducted by I&I NSW to investigate the effects of heating on hay.

Two batches of hay with high moisture content (approx. 30 per cent) were made into 1.2 m diameter round bales and their weight, temperature and feed quality were monitored over time.

The first batch of hay comprised two round bales of grassy lucerne.The second batch was two round bales made from ryegrass with seed heads emerged.

Samples were taken before and after baling, and after heating. Temperatures inside the bales were monitored for seven months after baling.

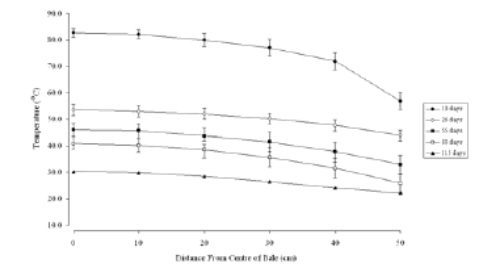

In the lucerne bales temperature was recorded at 10 cm intervals along the axis of the bales. In the ryegrass temperature was only monitored in the centre of the bale.

Temperature within the bale

In both batches of hay, temperatures peaked two to three weeks after baling. Peak temperatures in the middle of the bale were 83°C for lucerne and 89°C for ryegrass.

In the lucerne (figure 1) the temperature was generally 10°C to 15°C higher in the middle of the bale compared to 10 cm from the bale surface (i.e. 50 cm between middle and outer temperature measurements).

At the peak temperature of 83°C in the lucerne bale, there was a 30°C difference between the middle and outer temperature readings. Bales cooled to ambient temperature after approximately five to seven months (data not shown).

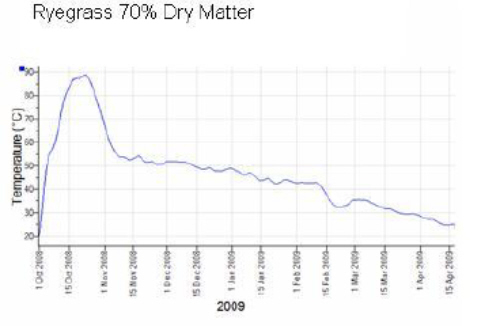

Temperature changes for the ryegrass hay are shown in figure 2. Temperatures increased quickly to a peak then fell quickly to approximately 55°C, followed by a period of five to seven months of slow cooling to ambient temperature.

Feed quality changes after heating

Heating of hay without burning is often thought by livestock producers to be beneficial, because it increases palatability of the hay. However, while palatability and potential intake may be increased, feed value of the hay is likely to be reduced.

Heating causes changes in the chemical structure of the hay which reduce its feed quality. Chemical bonds form between carbohydrate and protein, reducing metabolisable energy content and protein availability. The factors determining the extent of the reduction in feed value are not often fully understood.

As part of the trial, hay samples were analysed to measure changes in feed quality.

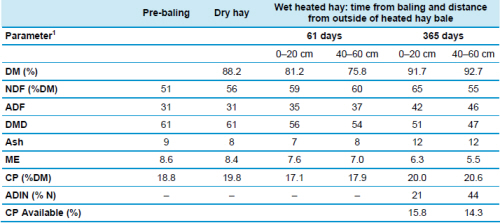

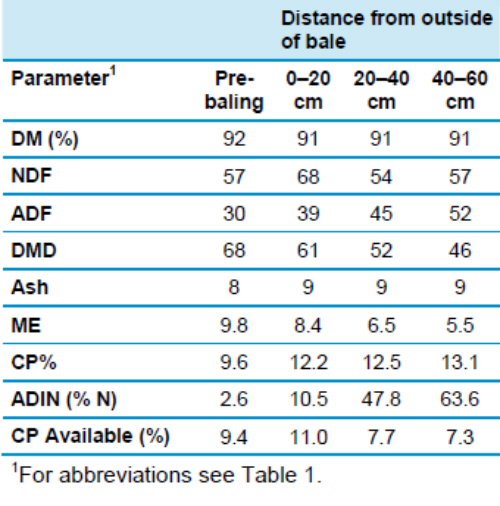

Feed quality of hay declined with heating, as measured by a number of feed parameters. Metabolisable energy (ME) declined as hay temperatures increased and with increased duration of heating, so the centre of each bale was hottest for longest and had the greatest drop in ME (Tables 1 and 2).

Crude protein (CP) content as a proportion of the whole bale DM increased slightly over time, indicating a greater loss of the non CP fraction, most likely WSC.

Acid detergent fibre (ADF) is a measure of the cellulose and lignin in forage. ADF increases with plant maturity. Acid detergent insoluble nitrogen (ADIN) is the amount of nitrogen bound to ADF and is an important component to consider with heated hay. ADIN is expressed as a proportion of total nitrogen (percentage N) and generally cannot be digested by animals.

An ADIN value greater than 12 per cent usually indicates some level of heat damage. While some proportion of ADIN formed through heating may be digested by animals (McBeth et al., 2001), the overall digestibility of CP is decreased when ADIN is increased (Coblentz et al., 2010).

The ADIN component of the lucerne and ryegrass hay increased following heating. The greatest effect was recorded at the centre of the heated ryegrass bales which were hottest for longest and had an ADIN of 63.6 per cent. Assuming that up to 30 per cent of this ADIN may still be available to the animal, this still indicates that the CP available for digestion would be reduced following heating (Table 2).

When excessive heating occurs (>38°C) amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein, react with sugars to become less degradable or less digestible. This reaction also occurs when cooking to brown meat or caramelise onions. The effect on hay is similar, with heated hay becoming caramelised and quite palatable to livestock. However, heating means the hay has lost energy and the Maillard Reaction means it has lost digestible protein.Browning reactions also produce more heat which can eventually lead to spontaneous combustion

Bale Weight

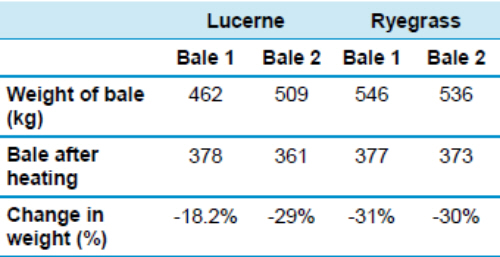

Although bales looked ‘normal’ on the surface, they lost between 18–31 per cent of their original weight following heating (Table 3).

Summary

Heating of hay following baling of high moisture lucerne and ryegrass resulted in a decrease in both energy and digestible protein of the hay. Combined with a loss of total dry matter in the bales this represents a significant loss of overall feed value of the hay. Producers should be aware of the potential losses of both dry matter and hay quality if they bale hay with a high moisture content.

September 2011