Unmasking the Canadian Cattle Crisis

1989 was a pivotal year for the Canadian beef and cattle sectors. A new market structure held aloft a promise of modernisation, globalisation and sector efficiency. Only now are the full effects coming to light and with them the realisation of what this promise really delivered, writes Adam Anson, reporting for TheCattleSite.Today's world of Canadian cattle is completely different to the one that existed before 1989. Not only are the companies that dominated that age gone, but also the landscape which they evolved on has been moved.

According to a report by the Canadian National Farmers Union - The Farm Crisis and the Cattle Sector: Toward a New Analysis and New Solutions - in Alberta alone there were 17 medium-sized beef packing plants in 1978. By today’s standards they may be considered too small, too inefficient, and too numerous to survive. "Most killed fewer than 2,800 cattle per week, whereas today's largest Canadian plants can each kill 28,000 per week", says the report. Despite this, the report claims that those plants still managed to pay farmers double what today’s mega-plants are paying. So where have the benefits of efficiency gone?

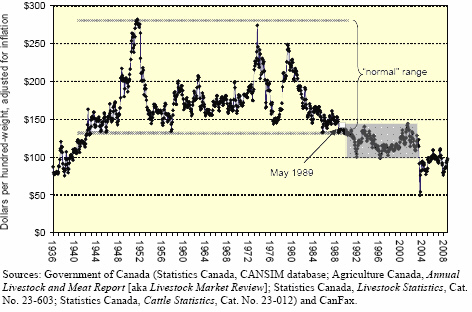

Canadian cattle prices began to fall immediately after 1989, yet many farmers still experienced good returns from their operations throughout the next decade, leading analysts to question why this prosperity continued in the face of falling prices? The answer is that grain prices also experienced an unprecedented downward shift in 1989. As these production costs decreased, the increasing profits offset falling returns, masking the true affects. But now that feed prices are rising they threaten to uncover the real problem.

January 1936 – August 2008

According to CanFax, prior to 1990 Canadian beef and cattle exports volumes were below 200 million kilograms and values around a half-billion dollars. However, between 1990 and 2003, Canadian exports increased five-fold, on a volume basis, and eight-fold, on the basis of dollar value. These figures portray spectacular performance. However, over the same period farmers’ prices for feeder and fed cattle were collapsing. average prices for recent years are half the values that prevailed pre-1989.

In 1989, a process of rapid continental integration took place between the US and Canada. In January 1989, Canada implemented the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. In May, Cargill opened its High River, Alberta, beef packing plant. This entry marked a dramatic acceleration in the transfer of control from a large number of Canadian-based packers and plants to just two US-based corporations that have concentrated production into a few huge plants.

According to the Canadian NFU, in the same period Canada began ramping up cattle and beef exports, mostly to the US. As the industry adapted to these new markets it soon became apparent that it had grown to depend upon them. This overdependence of the industry contributed to huge costs - including BSE losses, running into billions, price discounts relative to US cattle, traceability system costs, Country Of Origin Labelling (COOL), and risks of future border closures.

- Ban packer ownership and control of cattle, and require that all cattle go through independent auctions or be sold by fixed-price contacts with full disclosure of terms.

- Restrain packer power and reverse concentration.

- Decouple vertically integrated packers.

- Examine and restrain retailer and wholesaler power.

- Succeed in creating farmer-owned packing capacity.

- Tailor food safety regulations to encourage local abattoirs.

- Build collective marketing agencies.

- Test for BSE and ban artificial hormones.

- Dramatically reduce antibiotic use.

- Develop markets for grass-finished beef within Canada and North America.

- Embrace country-of-origin labelling.

- Focus on Local Food.

- Better balance Canadian beef production with domestic consumption.

- Get public money into farmers’ hands immediately.

- Give farmers a choice among cattle organizations to fund.

- Use government policy tools to encourage appropriate-scale family farm production.

NFU's 16 Steps to Turn the

Sector Around

At about the same time—as part of the integration, Americanisation, and corporatisation of the Canadian cattle and beef systems—levels of captive supply in Canadian feedlots rose. Captive supply is a tactic whereby packers own or control cattle that are being fattened in feedlots in preparation for slaughter. Captive supplies give packers an option: in any given week, packers can bid on cattle from independent feeders or packers can utilize their own cattle. Captive supplies give packers significant power to push down prices of finished cattle and, thus, to push down prices of feeder cattle and calves.

Giving an assessment of captive supply, Bob Peterson, former Chairman of IBP (now Tyson), said: "There is a quiet trend towards packer feeding and it is much, much bigger than you think it is...Do you think this has any impact on the price of the cash market? You bet!... In my opinion the feeder can’t win against the packer."

The NFU report explained that the places where profits are created and where they are captured often are not the same places. "Profits are created as a result of efficiencies; profits are captured as a result of power. Thus, because market power shifts can trump efficiency gains, even the most efficient can be left bereft of profit."

It was during this period of global integration that the relative power-balance between those who raise cattle and those who buy and process them shifted, in favour of the latter. Because this occurred almost simultaneously on both sides of the US/Canadian border, the effects reverberated around the globe.

The NFU calls for a re-balance of power, but restructuring a sector is not a simple prospect when you first have to dismantle a system manipulated by those in power. "One of the main impediments is the fiction of free, fair, and open markets—", claims the report. "In an age of captive supplies, two-packer control, giant grocery chains, and packer-owned auction yards, the “free market” has become one part nostalgia and one part parody."

The report goes on to describe a progression developed and popularised by a more sophisticated, up-to-date, and business-like assessment of market realities. As the former CEO of agribusiness giant Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) famously said in the early years of this decade:

The free market is a myth. Everybody knows that. Just very few people say it. If you're in the position like I am and do business all over the world, and if I'm not smart enough to know there's no free market, I ought to be fired. . . . You can’t have farming on a total laissez-faire system because the sellers are too weak and the buyers are too strong.

Further Reading

| - | You can view the full report by clicking here. |

December 2008