How We Created and Can Address the ‘Super Rat’

ANALYSIS - Sustained, prolonged and continuous rodent baiting protocols have resulted in the rapid development of ‘super rats’.The problem is now affecting large parts of the world, especially Britain and Europe, although many farmers and even some professional pest controllers are oblivious to the issue.

By intensively distributing bait and not evaluating efficacy, farms and businesses are contributing to rodents developing resistance to the most recent generation of rodenticides. However, when inspections at baiting stations reveal bait to have been eaten, many are satisfied that rodent control is being achieved.

Industry experts say there are questions that should be asked:

- What ate the bait?

- If it was a rat, was the rat resistant?

Why are Rats a Problem?

Rats can pose a disease threat to humans and animals. They carry an array of worms, bacteria and protozoa, including Leptospira spp, known to cause Weil’s disease.

Studies have found 63 per cent of UK rats carry Cryptosporidium bacteria, which causes gastrointestinal illness in humans and farm animals and a third carry Toxoplasma gondii, which can cause abortion and barrenness in sheep.

As a result, countries commonly impose legal requirements on organisations involved with producing, preparing, storing or retailing food to control rodent populations effectively.

A Welfare Issue

Resistant Against What?

The industry’s most common method of poisoning a rat is through the use of anticoagulant rodenticide (AR). The first case of resistance in Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) was found in Scotland in 1958.

AR products work by depleting vitamin K, which is responsible for clotting in the blood, leading to progressive haemorrhages. Requiring several days to kill a rat, many regulators consider these products ‘markedly inhumane’.

Now on the market for 30 years, the second generation of anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) are seeing resistance problems after taking over from warfarin, a first generation anticoagulant rodenticide (FGAR) product, in the late 1970s.

There is currently no known resistance to the three most potent SGARs - brodifacoum, difethialone and flocoumafen.

Chemicals Available

- FGAR e.g. chlorophacinone, coumatetralyl, warfarin – Resistance widespread and increasing

- SGAR e.g. difenacoum, bromadiolone, brodifacoum, flocoumafen – Resistance is occurring and increasing. Brodifacoum and flocoumafen are currently allowed indoors under ‘pulsed baiting’ and this makes them largely useless for rat control. Soon these will be allowed for use ‘in and around buildings’ and in ‘open areas’ by trained professionals because of increasing resistance to difenacoum and bromadiolone.

Resistance to warfarin, the first generation product, was recorded in Norway Rats in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, UK, Canada, US, New Zealand and Korea in 2005.

Environmental Impacts

Residues of SGARs are being found in a variety of wildlife, which either ingest bait themselves or prey on an animal that has eaten bait.

Hedgehogs, weasels, stoats, barn owls, sparrowhawks, kestrels and peregrine falcons have all been monitored showing high rates of AR residues in sampled wildlife populations, although the actual impact on non-target species is unknown.

Sparrowhawks are notable for exemplifying a new exposure pathway as they take almost no rodents, feeding mostly on small passerine birds taken on the wing. Experts think residues are passing into sparrowhawks either via small prey birds or snails/slugs that have either eaten spilled bait, or on occasional cases in small birds, actually eaten bait from bait boxes.

Non-target Species

Another issue is the level of bait eaten by non-target species. Baiting stations on farms, designed to be accessed by rats, are thought be easily breached by non-target species such as voles and field mice.

Studies of barn owl pellets have given credence to this theory as 90 per cent of surveyed owl pellets have been found contaminated with ARs. With barn owl diets thought to consist of less than one per cent rat or house mouse – the species targeted by AR baiting – there is a high chance of field mice, voles and bank voles of eating bait as these animals feature more prominently in barn owl diets.

Widespread and Spreading

Five Resistant Mutations

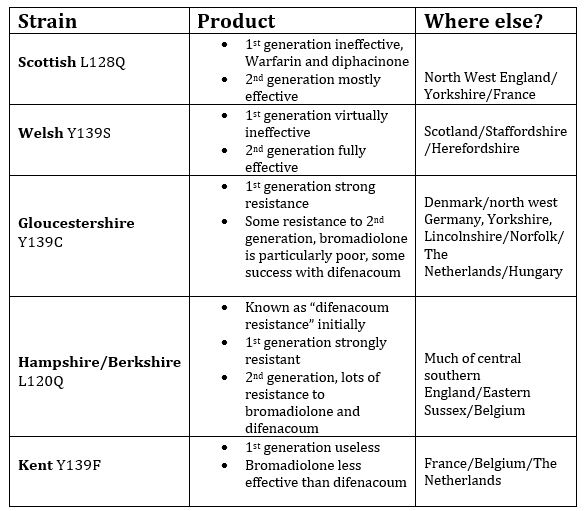

There are many resistant rat mutations around the world but five are present in the UK and have been proven as limiting AR efficacy – L128Q (Scottish), Y139S (Welsh), L120Q (Hampshire/Berkshire), Y139C (Gloucester) and Y139F (Kent).

The UK differs from some EU countries in that it has virtually all known resistance strains, although knowledge of geographical spread is patchy.

France has all five strains, with the most common strain being Y139F. Belgium and Holland are also known to have this strain and it has been found in the UK, but only in Kent and East Sussex so far.

Main Strains of Resistance

England's Problem

Of particularly note in the UK is the development of L120Q, believed to be a homegrown mutation, and Y139C.

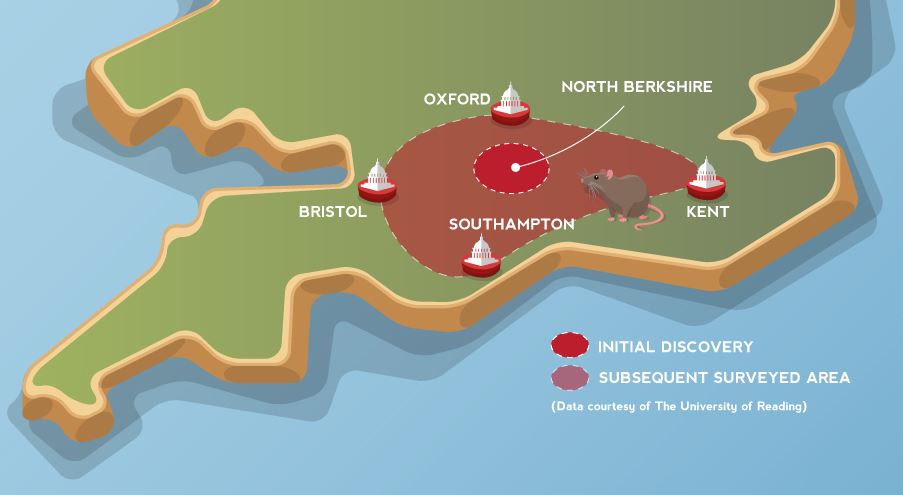

University of Reading monitoring has tracked the extent of L120Q resistance across the whole of central southern England after starting out on a handful of farms in north Berkshire.

Testing has stretched as far as Oxford to the north, Bristol to the West, Southampton to the south and across to Kent, finding very few non-resistant rats across the whole area.

A second mutation, Y139C, is much more dispersed and found in four regions – Dumfries and Galloway, Yorkshire, Norfolk and Gloucestershire. It is notable that the major ports of Stranraer, Hull, the Norfolk coast and Bristol are within the resistance zones.

A pocket of the Y139C mutation has existed for around 30 years in North West Germany, an area of high SGAR use. This strain is also very widespread across Denmark.

There are two resistant types of UK house mice – L128S and Y139C – which can be addressed indoors with brodifacoum, flocoumafen and difethialone. There are reports of resistance in bromadiolone but difenacoum remains largely efficacious.

Bait Shyness and Neophobia

After four centuries or more of being poisoned, rats have developed neophobia – the fear of new objects. This has a limiting effect on trapping efficacy and can, in early stages of baiting, also result in rats avoiding anticoagulants.

In time, rats slowly overcome their fear and non-resistant rats consume enough bait to be killed. Mice, in contrast, aren’t believed to be neophobic.

The issue of “bait shyness”, however, is generally not considered relevant for rats and anticoagulants, as they work too slowly to cause rats to react to bait in this way.

Shyness is the term for when a rat avoids something following the onset of an unpleasant symptom in a matter of hours. Anticoagulants work on a timescale of days.

Monitoring has shown rats tend to feed in large bouts, typically at the beginning and end of night. This is affected by social hierarchy within rat populations, with dominant rats forcing subordinate rats to squeeze feeding into early daylight hours. Some say this is reason for pulsed baiting to be deployed.

What Needs to Change

Many farms are ideal places for rats to inhabit as they offer the two must-haves for rodents – harbourage and food.

Minimising access to animal feed, removing the opportunity for rodents to crawl within structures and tidying farm yards are seen to have an important role to play in managing rat infestations sustainably.

Prevention of rat immigration from other locations is also key. Clearing rats from a farm can allow others to come, whether from neighbouring farms, hedges or bodies of water.

Judicious use of rat bait is recommended as this means regular and large quantities of bait are eaten by rats. This means using bait when clearly indicated and most importantly stopping when infestation is under control.

Comprehensive guidelines have been devised by the Campaign for Responsible Rodenticide Use (CRRU). CRRU’s UK Code of Best Practice can be downloaded for free.

Stemming from this work, a new stewardship scheme is set to change rules governing the sale and licensing of rat bait from the summer of 2016, offering farmers the opportunity to learn about the issues of rat control and demonstrate they know how to use rat bait effectively and safely to reduce exposure to non-target animals.

Further Reading

Access the CRRU Code of Best Practice here.

Thanks go to Dr Alan Buckle, University of Reading for guidance and help with the article

Michael Priestley

News Team - Editor

Mainly production and market stories on ruminants sector. Works closely with sustainability consultants at FAI Farms