Is it Worthwhile Cooling Dry Cows?

Farmers cooling cows through the dry period can expect them to produce more milk, heavier calves and have fewer health problems, say two University of Florida researchers.Take home messages

- Dry cows also suffer from heat stress; cooling dry cows improves production and health of the cow and calf.

- Cool the entire dry period if possible.

Heat stress is a well-recognized environmental factor limiting production, reproduction and health of dairy cows during lactation, according to Professor Geoffrey Dahl and Dr Saho Tao of the University of Florida's Department of Animal Health.

However, they ask - what about the dry period?

Compared with lactating cows, dry cows generate less metabolic heat and have a higher upper critical temperature. Thus, heat stress abatement in dry cow management has always been overlooked. Research shows that it substantially influences future performance of the cow and calf, however.

Dry Period Cooling Affects Milk Production, Feed Intake, and Body Weight

Heat stress abatement during late gestation increases milk production in the subsequent lactation, writes Prof Dahl and Dr Tao. Several factors affect the effects of cooling dry cows on subsequent milk production. Duration of cooling during the dry period may have an impact on subsequent lactational performance.

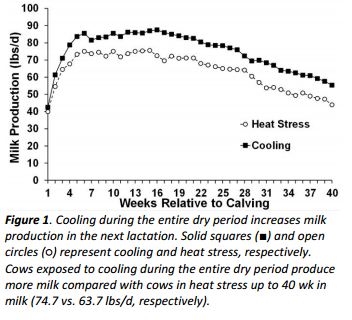

Cooling during the close-up period (last 3-4 wks of gestation) slightly improves milk production in the next lactation by 3.1 lbs/d relative to those who don’t receive cooling. In contrast, cows cooled during the entire dry period produce ~11 lbs/d more milk (Figure 1) during the next lactation compared with those without prepartum cooling.

Cooling methods during the dry period also influence the effectiveness of heat stress abatement on subsequent milk production. With limited cooling, such as shade or short interval soaking in the middle of the day, only modest increases (2.4-6.6 lbs/d) in subsequent milk production were observed. However, when more extensive cooling (shade, fans and sprinklers) was provided to dry cows, milk production in the subsequent lactation was again significantly improved (~11 lbs/d.

Similar to lactating cows, heat stress also decreases dry matter intake of dry cows. When housed in a freestall barn through the entire dry period, cows under evaporative cooling (fans and sprinklers) had a ~15 per cent increase in dry matter intake compared with those without cooling during summer. As a result, cooled cows gain more body weight during the prepartum period. In early lactation (first 2-3 weeks postpartum), prepartum cooled cows consume similar amounts of dry matter but produce more milk, thereby achieving a higher feed efficiency relative to prepartum non-cooled cows.

However, as the lactation advances, prepartum cooled cows will consume more feed relative to non-cooled cows in order to meet the higher nutrient demand of the increased milk production.

Dry Period Cooling Affects Immune Function and Health

In addition to milk production, heat stress during the dry period also affects the immune function of animals during the transition period. Recent studies suggest that cooling during the entire dry period improves immune cells’ proliferation and killing ability when exposed to pathogen ex vivo in early lactation.

These studies are of importance because the enhanced immunity, especially for neutrophil function, plays important roles in the combat of pathogens involved in mastitis and metritis. Thus, it is expected that cooling heat-stressed dry cows improves animal health and decreases disease incidence during the transition period. However, the direct comparison of disease incidences between prepartum cooled and non-cooled cows in the next lactation is still not available.

Dry Period Heat Stress Affects Calves

Late gestation heat stress also shortens the cow’s gestation length. Relative to heat stress abatement, non-cooled heat-stressed cows during the entire dry period have ~4 days shorter gestation length. Additionally, calves born to heat-stressed cows are smaller and prepartum cooling increases calf birth weight about 13 per cent (11 lbs).

Additionally, maternal heat stress also compromises the offspring’s immune function. Passive immunity is important to the survival of neonatal calves and is altered by maternal heat stress. Calves born to non-cooled heat-stressed cows during the dry period have lower serum IgG concentration and absorption efficiency relative to those from cooled dams.