Learning & Profiting from Animal Welfare Trends

New definitions and expectations surrounding welfare also carry strong value-added opportunities for the livestock industry, says Dr. John Webster in the proceedings from the Livestock Care Conference, held by Alberta Farm Animal Care.England’s largest supermarket paying dairy farmers 15 to 20 percent more to improve welfare. McDonald’s leading the way with higher livestock welfare standards. Farmers worldwide taking steps to integrate welfare into quality assurance schemes.

|

Lack of Awareness |

These developments are signals of monumental shifts in expectations and approaches surrounding animal welfare, each with major implications for the livestock industry.

Helping make sense of the trends and what they mean for producers both in Europe and North America was Dr. John Webster of the University of Bristol in England, who delivered a presentation on the subject at the Livestock Care Conference, April 4 in Red Deer. The conference was hosted by Alberta Farm Animal Care (AFAC), a partnership of Alberta’s major livestock groups with a mandate to promote responsible, humane animal care within the livestock industry.

“We have reached a pivotal time in animal welfare,” says Webster. “This includes many changes and challenges. But for the livestock industry, the good news is that it also includes profit-generating opportunities for farmers related to producing a value added product, which are critical to their survival in a competitive environment.”

This assessment and the details that support it mean a lot coming from Webster. One of the world’s leading authorities on animal welfare issues, Webster was a founding member of the UK Farm Animal Welfare Council and is the original proponent of the "five freedoms" concept that has become central to emerging animal welfare policy and strategies worldwide.

While he sees that animal agriculture still has substantial room to improve when it comes to implementing systems of continual welfare improvement, strong progress is being made and innovations are gaining steam in many countries, particularly in Europe but also in North America.

“I wouldn’t want to fool anyone by saying all steps to improve animal welfare will improve profitability for livestock producers,” says Webster. “But the way things are moving, I would say to the livestock industry that being self protective and saying there’s nothing wrong is not your best solution. There is an opportunity there in terms of value-added products. Just think: if we can do it better, they’re very likely to pay us.”

What is welfare science?

New definitions, new expectations

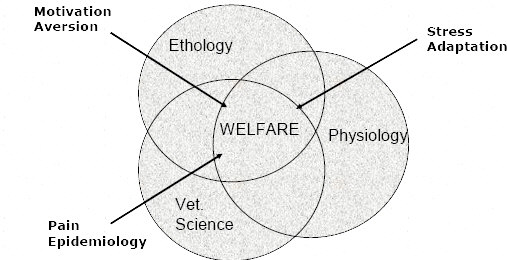

Critical to understanding the new trends in animal welfare is understanding the concept of welfare itself, says Webster. This is important not only to society in general and to the livestock industry, but also to the growing ranks of ‘welfare scientists’ who will play an essential role in the ongoing development of welfare standards.

In this context, the traditional questions and concepts related to welfare have undergone a major updating, he argues. For example, the typical questions traditionally posed by welfare scientists to assess animal welfare are today inadequate. These include questions such as: Is the animal living a normal life? Is the animal fit and healthy? How does the animal feel?

“If the first question was adequate, we would be saying all swine should live in the woods. If the second was adequate, we’d be fine with gestation crates so long as the animal was healthy. The third question is probably the closest to being useful, but is still not quite refined enough to provide a comprehensive assessment of welfare.”

For a modern definition, Webster supports one derived and extended from earlier definitions by Dr. David Fraser of the University of British Columbia and Donald Broom of Cambridge University. This definition states that animal welfare is “The physical and mental state of a sentient animal (one sensitive in perception or and feelings) as it seeks to cope with environmental challenge.”

“Welfare then doesn’t just mean feeling good,” says Webster. “It is the full spectrum from feeling very good to genuine suffering. And it is defined by both its physical and emotional state.”

The concept of sentience is key to the definition, he notes. In pending European Community legislation, farm animals are recognized as sentient creatures. “This reinforces that farm animals are not simply commodities. They are sentient creatures and we must respect their sentience.”

Webster makes a distinction between animal welfare and animal well-being. Animal welfare, he says, covers the full spectrum of animal feeling. Animal well-being, on the other hand is defined by an ability to have sustained mental and physical health, to avoid suffering and to generally feel good about life.

“For farm animals, this would include things like comfort, companionship and security, which are particularly important to animals in a herd species,” says Webster.

The aspiration for those looking after farm animals, he suggests, should be to promote a sense of well-being within the context of a healthy agricultural industry. This aspiration may not be practical to achieve all the time, but the goal should be to realize it “as much as possible” and to continually strive for improvement

A Sentient View of the World

Feelings that matter

Sentience itself too, requires an updated definition in the context of animal welfare, says Webster, suggesting that a useful definition is “feelings that matter.”

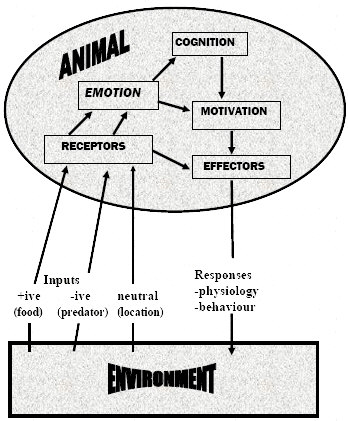

A sentient animal will interpret stimuli at three levels, he explains. These include a basic reflex level, a second emotional level achieved by all sentient animals and a third cognitive level achieved by humans and to some degree by most sentient animals.

Sentient animals do not just live in the present, he says. They are motivated, by emotion and cognition, to action. “The strength of motivation to action is a measure of how important these things are to them.”

This concept is a foundation for an increasing number of new studies in animal welfare, which study animal responses to stressors and other stimuli as a means of validating issues of animal pain and suffering and also of gauging their relative importance to animal welfare and well-being.

Earlier pioneering studies in this vein have shown, for example, that animals will self-medicate and perform similar coping actions in response to various negative stimuli.

“If the coping action is successful, the sentient animal with cognitive capacity will learn from it and repeat it under the same circumstance,” says Webster. “This is evidence of a highly sentient animal.”

Fear & Anxiety

The cost of coping

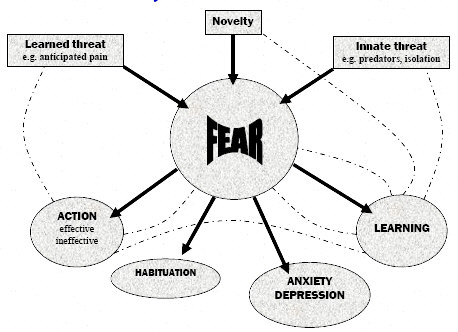

From an animal science point of view, Webster suggests the best studies today are those that recognize the “cost of coping” for an animal rather than simply an alarm response, since some animals may not respond greatly if they have learned the “cost” of doing so is not worthwhile or not effective. “It’s much more useful to measure the stress-specific cost of coping.”

This leads to a definition of suffering, notes Webster, which he defines as a state where an animal cannot cope, or has extreme difficulty coping with a stressor. “This occurs when the stressor is too prolonged or simply too much, or because the animal is unable to respond in a way that will improve how it feels.” Examples he says are swine in gestation stalls or hens in battery cages, which are unable to respond in a way that will improve their condition.

Awareness of this is key to recognizing welfare issues and seeking improvements, he says.

“The old way of thinking is that animals can experience pain, but that is just about it. Today we increasingly recognize that suffering is much more than just pain and that animals have this broader capacity to suffer.” They also have strong capacity for a higher quality of life, to which those responsible for animals must aspire.

The bottom line of the new definitions and thinking on welfare is that expectations are rising, says Webster. “Suffering and pleasure are defined by the capacity to feel, not the capacity to think. And we cannot assume that the capacity to feel is proportional to intelligence, as we define it.” This brings animals on more of a level plane to humans in terms of what society considers acceptable in terms of being subject to pain and suffering.

Marketplace driving new systems

For the livestock industry, this means expectations for how farm animals are treated are also continuing to rise. “We recognize that farm animals are sentient and have capacity to suffer,” says Webster. “This raises the bar for our responsibility in taking care of these animals.”

While legislation for improving welfare has been relatively slow to reflect these new expectations, the free market, operating through the likes of McDonald’s and other major food retailers is having a major impact.

As a result, animal welfare is increasingly being viewed as an important component of emerging quality assurance schemes. “Increasingly and inevitably in Europe now, quality assurance schemes are including criteria for assessment of animal welfare,” says Webster. “And if animal welfare is not up to the standards of the scheme, the farmer will be lost from the scheme. Many of these schemes are driven by supermarkets and big retailers who are marketing their products on a high welfare platform because consumers are making choices based on that platform.”

Webster portrayed new expectations as moving toward a "virtuous bicycle" model, where incorporating welfare standards as part of food quality assurance can deliver benefits to all parts of a "fork-to-farm" market-driven chain, including animals, producers and consumers."

The front wheel of the bicycle includes a system for monitoring animal welfare, he explains. The back wheel is a public component that includes a review and feedback to the producer “This model will probably be based on an animal-based, external assessment leading to a constant cycle of action and review to achieve a state of steady improvement of animal welfare,” says Webster.

“At the moment, this is not really happening. There are monitoring systems, some of them are quite good, but they’re not yet leading to action. With time, they will.”

Fast-changing times

As the marketplace leads the way, policy and regulation is also making headway, he says.

Ideas developed by Webster such as the Five Freedoms are now being taken up in Europe in a big way and are expected to become European standards within the decade. This will place pressure on North America to adopt similar approaches.

“What we’re heading towards is an environment where the marketplace expects high welfare but also expects to pay more to those who supply that high welfare.”

If Europe is an indication, trends are moving quickly, he observes. And pressure is not just on livestock producers to adjust but on the food system as a whole.

In one recent development, the UK’s largest food retailer, the Waitrose supermarket chain, introduced a high welfare scheme that included granting five year contracts to dairy producers that included a 15 to 20 percent increase in the price of milk.

“The public perception was that producers couldn’t improve welfare because the supermarkets were not paying them enough and that led to the scheme,” says Webster. “That’s something we wouldn’t have seen happen 10 years ago.”

Further Reading

| - | You can view other features from the 2008 Livestock Care Conference by clicking here. |

April 2008